Viking Bread c. 850 CE

Historical Context

Bread has been a part of the human diet since at least the time of the Old Testament. This is somewhat surprising since bread requires multiple steps and a good deal of time to make—growing the grain, reaping it, threshing to remove the hulls, grinding the grain into flour, preparation of the dough, rising the dough and producing a yeast source for leavened breads, and baking. Despite this, bread became a staple food in many cultures and a major source of calories for humans.

In Viking culture, usually considered to be 793-1066 CE, bread was more of a luxury and a symbol of wealth.[1] Most archeological sites of Viking settlements found breads and several had ovens. Many of the finds were grave goods, and those breads were small, flat circles and unleavened. In finds outside the graves, they found small balls of bread, large flatbreads, and something that might have been a pretzel.[2] Some of these had small bubbles inside, indicating yeast risen breads. There are also runic inscriptions referring to bread.[3] Bread rounds are mentioned in the sagas as being used as plates.[4]

Since several sites did not have ovens, it is likely that other methods of baking were employed: baking the bread on a heated flat stone or pottery shard, baking in an iron, soapstone,[5]or pottery pan on top of hot coals, and even placing the loaves directly in the embers. The main method of cooking all foods in this period was in large cooking pits, in iron, soapstone or pottery cookware. Leavening was achieved either from the barm or dregs from brewing or by capturing wild yeast in a sourdough.[6] Multiple grains were found. Wheat, rye, oats, and barley were found, and most of the breads had two or more grains in each loaf, though wheat predominated. Millet was found at Hedeby, which was likely obtained in trade from Slavic areas.[7] At Birka, one of the breads found also contained legume flour, and flax seed.[8] Most of the barley was found in conjunction with brewing equipment, but some breads contained it as well.[9] The barley type was Hordeum vulgare, the variety still used most often in brewing today.[10] As barley was found in much larger quantities than all other grains, it appears that beer was valued highly. Jorvik was the only site where wheat was found in larger quantity than barley.[11] Einkorn (triticum monococcum), was probably the most common wheat, as it grows well in cool weather and poor soil and is an ancient grain that spread widely throughout Europe.[12] It was one of the first wheats to be cultivated. Millstones have also been found in many of the archeological sites. Hand querns were found at several sites among grave finds.[13] Fine tableware of pottery and glass vessels, amphorae, and Mediterranean, North African, Spanish, and Gaulish foodstuffs were found in graves in Jutland.[14]

The Vikings also had regular contact with Anglo-Saxon England—mostly through raiding their coasts, but also through trade. England was known for the fertility of their land, and the Viking raids of 9th C. led to “sharing” of grain and technology.[15] In England, bread was a staple food, and the production of grain and making bread were more sophisticated than in Viking towns and cities. Drying kilns were employed to roast grain, grain was stored in special buildings, and hand mills were used for grinding grain at home. Water mills were in use by the 7th C, and the Domesday Book documents 6000 water mills in England in the late 11th C.[16] Wheat was favored as the grain for bread, barley for beer and fodder. They also grew millet, oats, and probably rye.[17] By the end of the period, they had multiple varieties of wheat, the most common were “bread wheat” (triticum astivum), and “club wheat” (triticum compactum),[18] both of which are hybrids of einkorn wheat, which existed in England since 4000 B.C.E. and was cultivated since the Neolithic period.[19] “Bread wheat” is what we call “common wheat” today, and “club wheat is a closely related variant. Common wheat is the most frequently grown wheat of the modern era.[20] The gluten content may have been lower in the historical period, as was the case with most early wheats, and because modern flours often have gluten added. The English also baked both leavened and unleavened breads, and had yeast from the same sources as the Vikings: wild yeast in the air, barm from brewing, and the sediment left from brewing, which could be dried and preserved.[21] They baked in beehive shaped ovens that continued to be used throughout the middle-ages.[22]

Process

I decided to attempt Viking bread after reading the excellent article “Breads from the Birka Graves: An Experiment” by Marshal Taylor, published in Tournaments Illuminated, where he recreated the grave find breads. I decided to try my hand at recreating a bread more typical of what would be eaten at meals. I started by creating a barley sourdough. Barley, with its high sugar content, would be good for getting the yeast going. My first three attempts at bread were with 100% einkorn flour and a barley sourdough starter.

The first attempt did not rise at all after two hours. I ended up making some excellent crackers with it, and they did puff up from yeast action during the bake. I determined that einkorn needed a longer rise time.

[1] Serra and Tunberg, p15

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, p. 16

[4] Ibid. p. 24

[5] Ibid. p. 140, 24

[6] Ibid., p.24

[7] Ibid. p. 90

[8] Ibid. p.143

[9] Ibid, p. 15

[10] Ibid. p. 16

[11] Ibid., pp. 107, 15

[12] www.thoughtco.com/wheat-domestication-the-history-170669

[13] Serra and Tunberg, pp. 107, 143

[14] Gaskell and Carter, p. 496

[15] Hagen, Vol. 2, p. 11

[16] Hagen, Vol 1,pp. 11-13

[17] Hagen, Vol. 2, pp. 11-20

[18] Hagen, Vol. 2, p. 20

[19] www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-31648990

[20] http://en.wikipedia/wiki/Common_wheat

[21] Hagen, Vol. 1, p. 15

[22] Ibid., p. 17

Historical Context

Bread has been a part of the human diet since at least the time of the Old Testament. This is somewhat surprising since bread requires multiple steps and a good deal of time to make—growing the grain, reaping it, threshing to remove the hulls, grinding the grain into flour, preparation of the dough, rising the dough and producing a yeast source for leavened breads, and baking. Despite this, bread became a staple food in many cultures and a major source of calories for humans.

In Viking culture, usually considered to be 793-1066 CE, bread was more of a luxury and a symbol of wealth.[1] Most archeological sites of Viking settlements found breads and several had ovens. Many of the finds were grave goods, and those breads were small, flat circles and unleavened. In finds outside the graves, they found small balls of bread, large flatbreads, and something that might have been a pretzel.[2] Some of these had small bubbles inside, indicating yeast risen breads. There are also runic inscriptions referring to bread.[3] Bread rounds are mentioned in the sagas as being used as plates.[4]

Since several sites did not have ovens, it is likely that other methods of baking were employed: baking the bread on a heated flat stone or pottery shard, baking in an iron, soapstone,[5]or pottery pan on top of hot coals, and even placing the loaves directly in the embers. The main method of cooking all foods in this period was in large cooking pits, in iron, soapstone or pottery cookware. Leavening was achieved either from the barm or dregs from brewing or by capturing wild yeast in a sourdough.[6] Multiple grains were found. Wheat, rye, oats, and barley were found, and most of the breads had two or more grains in each loaf, though wheat predominated. Millet was found at Hedeby, which was likely obtained in trade from Slavic areas.[7] At Birka, one of the breads found also contained legume flour, and flax seed.[8] Most of the barley was found in conjunction with brewing equipment, but some breads contained it as well.[9] The barley type was Hordeum vulgare, the variety still used most often in brewing today.[10] As barley was found in much larger quantities than all other grains, it appears that beer was valued highly. Jorvik was the only site where wheat was found in larger quantity than barley.[11] Einkorn (triticum monococcum), was probably the most common wheat, as it grows well in cool weather and poor soil and is an ancient grain that spread widely throughout Europe.[12] It was one of the first wheats to be cultivated. Millstones have also been found in many of the archeological sites. Hand querns were found at several sites among grave finds.[13] Fine tableware of pottery and glass vessels, amphorae, and Mediterranean, North African, Spanish, and Gaulish foodstuffs were found in graves in Jutland.[14]

The Vikings also had regular contact with Anglo-Saxon England—mostly through raiding their coasts, but also through trade. England was known for the fertility of their land, and the Viking raids of 9th C. led to “sharing” of grain and technology.[15] In England, bread was a staple food, and the production of grain and making bread were more sophisticated than in Viking towns and cities. Drying kilns were employed to roast grain, grain was stored in special buildings, and hand mills were used for grinding grain at home. Water mills were in use by the 7th C, and the Domesday Book documents 6000 water mills in England in the late 11th C.[16] Wheat was favored as the grain for bread, barley for beer and fodder. They also grew millet, oats, and probably rye.[17] By the end of the period, they had multiple varieties of wheat, the most common were “bread wheat” (triticum astivum), and “club wheat” (triticum compactum),[18] both of which are hybrids of einkorn wheat, which existed in England since 4000 B.C.E. and was cultivated since the Neolithic period.[19] “Bread wheat” is what we call “common wheat” today, and “club wheat is a closely related variant. Common wheat is the most frequently grown wheat of the modern era.[20] The gluten content may have been lower in the historical period, as was the case with most early wheats, and because modern flours often have gluten added. The English also baked both leavened and unleavened breads, and had yeast from the same sources as the Vikings: wild yeast in the air, barm from brewing, and the sediment left from brewing, which could be dried and preserved.[21] They baked in beehive shaped ovens that continued to be used throughout the middle-ages.[22]

Process

I decided to attempt Viking bread after reading the excellent article “Breads from the Birka Graves: An Experiment” by Marshal Taylor, published in Tournaments Illuminated, where he recreated the grave find breads. I decided to try my hand at recreating a bread more typical of what would be eaten at meals. I started by creating a barley sourdough. Barley, with its high sugar content, would be good for getting the yeast going. My first three attempts at bread were with 100% einkorn flour and a barley sourdough starter.

The first attempt did not rise at all after two hours. I ended up making some excellent crackers with it, and they did puff up from yeast action during the bake. I determined that einkorn needed a longer rise time.

[1] Serra and Tunberg, p15

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, p. 16

[4] Ibid. p. 24

[5] Ibid. p. 140, 24

[6] Ibid., p.24

[7] Ibid. p. 90

[8] Ibid. p.143

[9] Ibid, p. 15

[10] Ibid. p. 16

[11] Ibid., pp. 107, 15

[12] www.thoughtco.com/wheat-domestication-the-history-170669

[13] Serra and Tunberg, pp. 107, 143

[14] Gaskell and Carter, p. 496

[15] Hagen, Vol. 2, p. 11

[16] Hagen, Vol 1,pp. 11-13

[17] Hagen, Vol. 2, pp. 11-20

[18] Hagen, Vol. 2, p. 20

[19] www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-31648990

[20] http://en.wikipedia/wiki/Common_wheat

[21] Hagen, Vol. 1, p. 15

[22] Ibid., p. 17

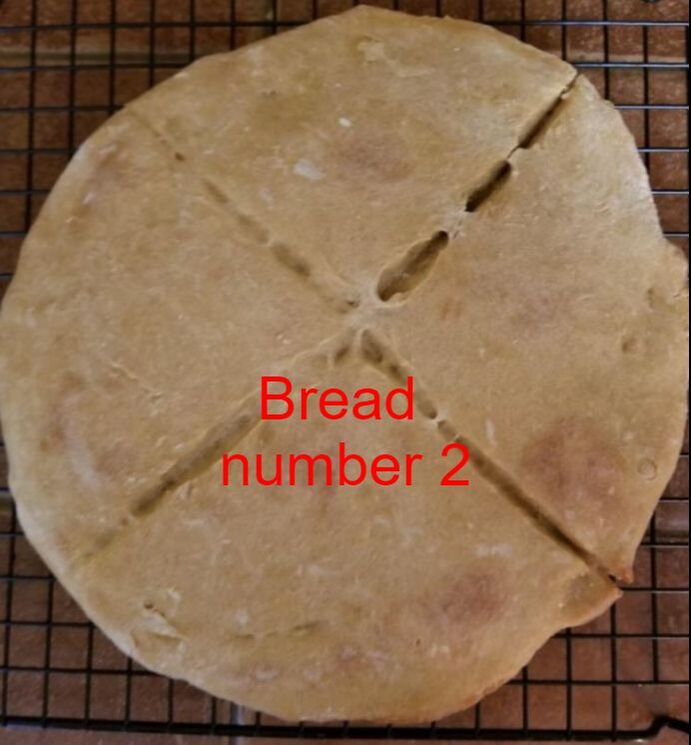

My second attempt rose a bit with a longer rise time, and I got a type of flat bread. I thought it was raw in the center, but once it cooled completely it was baked through, just very dense. I ate the edges, which were nice and crispy, and gave the rest to the birds, who had no problems with it. The flavor was quite good. I cooked this in a modern cake pan. I decided to switch to iron pans after this one to be more historically accurate and hopefully get better bakes.

My third attempt I proofed overnight in a warm oven, but it still didn’t look like it had risen much. It may have risen and then fallen. I kneaded it and gave it another two hours to rise. I did get a better rise, but it burned slightly on the bottom, and had a very thick bottom crust. However, once cut, it had obvious irregular air pockets, and it was cooked through. It had a nice texture and a good flavor; something between whole wheat and rye with a bit of sweetness. I considered this one to be a success. This one was cooked in an iron skillet.

My third attempt I proofed overnight in a warm oven, but it still didn’t look like it had risen much. It may have risen and then fallen. I kneaded it and gave it another two hours to rise. I did get a better rise, but it burned slightly on the bottom, and had a very thick bottom crust. However, once cut, it had obvious irregular air pockets, and it was cooked through. It had a nice texture and a good flavor; something between whole wheat and rye with a bit of sweetness. I considered this one to be a success. This one was cooked in an iron skillet.

|

read number four was a mixed grain bread of Common flour period reproduction[1] ( 1 ½ lb. unbleached all purpose flour, 7 oz. cake flour, 2 oz. whole wheat flour, and 1 oz. rye flour because the mill stones weren’t cleaned between grindings), all-purpose einkorn, and whole grain einkorn. It was seriously underproofed, and separated around the center. It was also raw in the center and had to be discarded. It was cooked in a cast iron Dutch over. Clearly this needed a longer rising time.

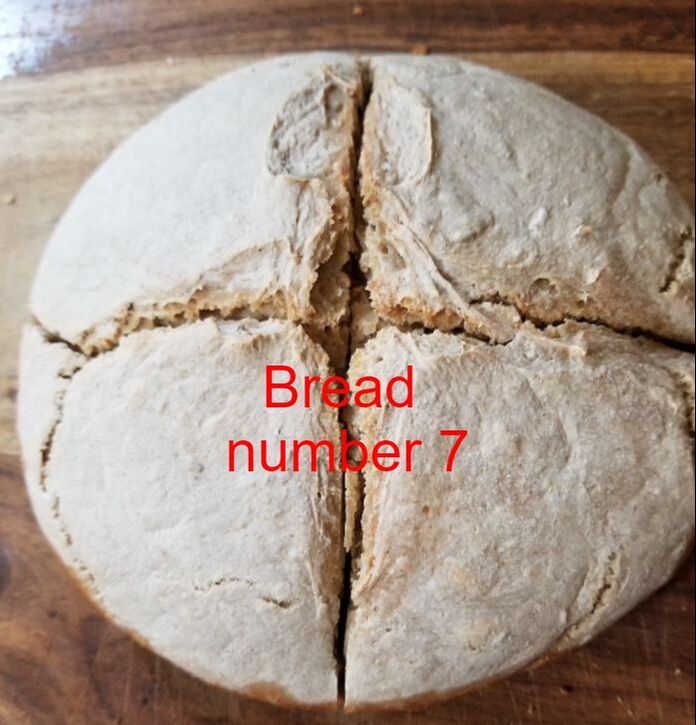

Bread number five was slightly underproofed, but was baked through, looked good, and tasted good. It was also a mix of the three flours, but in different proportions, and it had caraway seeds added. It was baked in an iron skillet. I decided to try this one again but with a longer rise. Bread number six was similar to number five, but with less whole grain einkorn. It was baked in a cast iron Dutch oven. It did not rise as well as I hoped, despite giving it very long rise times—3 hours for each rise. My starter had gotten very thick, and I had to add extra water to make it usable, so this might have been part of the problem. It rose fairly well, but failed to brown on top, and didn’t look good. It was cooked through and had good texture. It tasted quite good, and I saved half the loaf (in the freezer) for judging, just in case I couldn’t improve on it. For the seventh bread, I decided that the cast iron Dutch oven was a problem, and decided to do all further breads in the skillet, as those had produced the best results. I also decided to use both the sourdough starter and to try to reproduce ale barm, the foam that rises to the top of the vat in ale making. There is documentation that the Gauls were using ale barm to rise bread in the late Roman period.[2] For this I mixed water, active dry yeast, barley malt syrup, and a small amount of modern ale. The general look of this bread matches the few descriptions that exist from period, and if cut in two through the width, would make two bread plates, sturdy enough to support the weight of food on them. This is the bread that will be entered in the competition, as it was my most successful bread. My eighth and last bread was identical to the seventh, but without the addition of the “barm.” It failed to rise, and was so underproofed that it was inedible. At this point I was sure that my starter had become weakened, but I gave it one more try. That bread also failed to rise after 6 hours. Although my starter was clearly making CO2, it wasn’t enough to get breads to rise. This can happen with sourdoughs in general, but barley, not being a wheat, may have had difficulties that I did not foresee. There is no photo. Summary This was a great learning experience in many areas: working with sourdough, using ancient grains with low gluten, figuring out which heat levels, pans, and rising conditions work the best, and many more things. It was certainly frustrating that at least half of the breads were inedible. I have a whole new appreciation for modern yeasts. If I were to make Viking breads again, I would not use a barley starter, but would use one made from common wheat flour, which is lighter and higher in gluten. I might also work with some SCA brewers to get actual ale barm to use as a rising agent. I am happy that I got four breads that were edible and tasty, if not everything that I was looking for in a bread. I am quite satisfied with the entry bread in both looks and taste. The recipe for it can be found in the addendum. BIBLIOGRAPHY An Early Meal—A Viking Cookbook & Culinary Odyssey, Daniel Serra and Hanna Tunberg, 2013, ISBN 978-91-981056-0-5 A Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Food, Volume I, Ann Hagen, 1994 edition, ISBN 0-9516209-8-3 A Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Food, Volume II, Ann Hagen, 1995 2nd edition, ISBN 1-898281-12-2 “Breads from Birka: An Experiment.” Marshal Taylor, Tournaments Illuminated, Issue 213, 2020, pg. 25 The Complete Bread Cookbook, Ted and Jean Kaufman, 1969, Gramercy Publishing Co., USA War Fare, Bonnie Feinberg and Marian Walke, 2010, ISBN 978-0-578-06232-7 The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture, Ivan Gaskell and Sarah Anne Carter, eds., “Chronology and Time: Northern European Coastal Settlements and Societies, c. 500-1050,” Christopher Loveluck, 2020, ISBN 978-0-19-934176-4 www.lesleftsblogspot.com/2015/01/french-bread-history-bread-of-gauls.html “Pre- and Protohistoric Bread in Sweden, a Definition and Review,” Ann-Marie Hanson, Civilizations, no. 49, 2002, at http://Journals.openedition.org/civilisations/1432 www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-31648990 www.thoughtco.com/wheat-domestication-the-history-170669 http://dontwastethecrumbs.com/einkorn-sourdough-sandwhich-bread/ https://www.professorshouse.com/caraway/ Addendum Einkorn and Common Wheat Sourdough Bread ½ cup barley sourdough starter ¾ cup ale “barm” (1/4 cup ale, ½ cup water, 1 tsp dry yeast, 1 tsp malt syrup) 1 cup whole grain einkorn flour 2 cups common wheat flour mixture* 1 tsp salt 2 tsp caraway seeds** Lard for greasing bowls and pans Put the sourdough starter in a non-metallic bowl and add the barm mixture. Add the einkorn flour and 1 cup of the common flour mixture. Stir well for 5 minutes. Turn into a well greased bowl. Cover and rise 3 hours. Uncover and add the remaining flour, salt, and caraway seeds. Knead until the dough is smooth, about 5-6 minutes. Shape into a round loaf and place in a greased iron pan. Cover and rise until nearly double, 2-3 hours. Slash the top with a sharp knife in a cross. Bake in a preheated 400° F for 45 minutes. Cool in the pan for 5 minutes, then turn onto a wire rack to finish cooling. *This recipe comes from War Fare, and has been excellent in reproducing other breads and pastries. 1 ½ lb. unbleached all purpose flour 7 oz. cake flour 2 oz. whole wheat flour 1 oz. rye flour (because the mill stones weren’t cleaned between grindings) **Caraway seed (it is actually the fruit) is an ancient spice known since early Egyptian times, and was cultivated throughout northern Europe during the Viking period.[3] [1] War Fare, pp117-118 [2] Lesleftblogspot, citing Pliny the Elder, “In Gaul and Spain, where they make a drink by steeping [grain]... - they employ the foam which thickens upon the surface as a leaven: hence it is that the bread in those countries is lighter than that made elsewhere.” Found in Pliny the Elder, The Natural History of Pliny [3] https://www.professorshouse.com/caraway/ |