Beginning Costume; Period Patterns and Construction

Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 2007)

- Costumes as clothes

- Period style costumes are clothes and should meet all the requirements of mundane clothes

- Fit properly

- Comfort—as much as the fashion allows

- Protection from the elements

- Make us look good

- Clothes from any period can meet these requirements for any body type

- Period style costumes are clothes and should meet all the requirements of mundane clothes

- Fabrics--

- Manufacture in period

- Fabric was expensive relative to the cost of other items because it was labor intensive and took a long time to make

- Fulling—beating the fabric in water as part of the manufacturing process of linen and wool

- Softens the fabric

- Shrinks the fabric

- Bleaching agents can be added to whiten

- Types of fibers used in clothing

- Linen

- Almost all undergarments

- Some overgarments

- Wool

- Most overgarments

- Most outerwear: cloaks, hoods, hats

- Wool velvet—common for the upperclasses

- Wool felt—hats, cloaks

- Silk, silk brocade, silk velvet

- Very expensive—only for wealthy nobles

- Court garments, ceremonial garments, eccleastical garments

- Cotton

- Only common in the middle-east

- Some cotton blends were seen in Europe

- Fur

- Used as linings in clothing by the upperclasses

- Linings in hoods and cloaks

- Linen

- Fabric patterning and colors

- Colors—virtually all colors were available

- True black was difficult to achieve

- Gold and silver thread were used in some brocades—very pricey

- Patterns

- Prints as we know them today did not exist in period

- Patterns were woven in

- Stripes

- Checks

- Plaids

- Brocades

- Other patterns achieved through weaving techniques

- Colors—virtually all colors were available

- Manufacture in period

- Cut: period patterns

- Undergarments

- Chemise for women

- Shirt, drawers, and hose for men

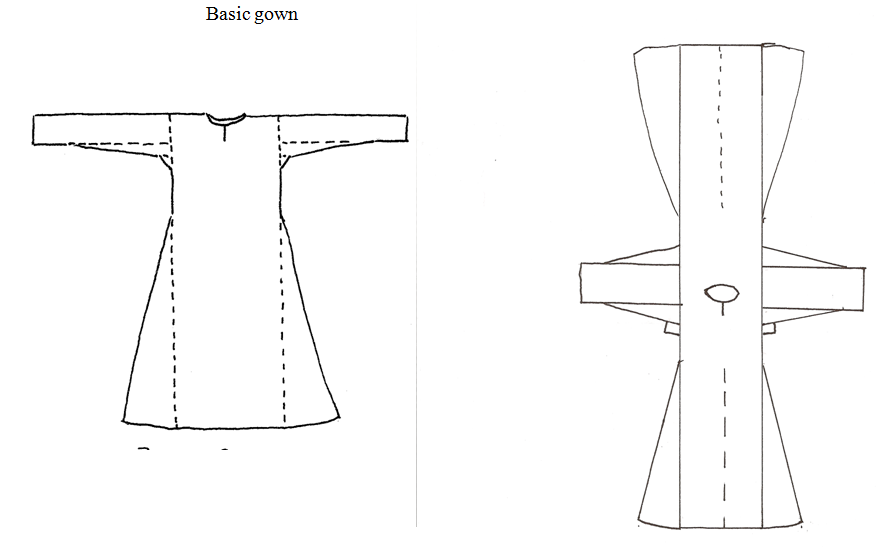

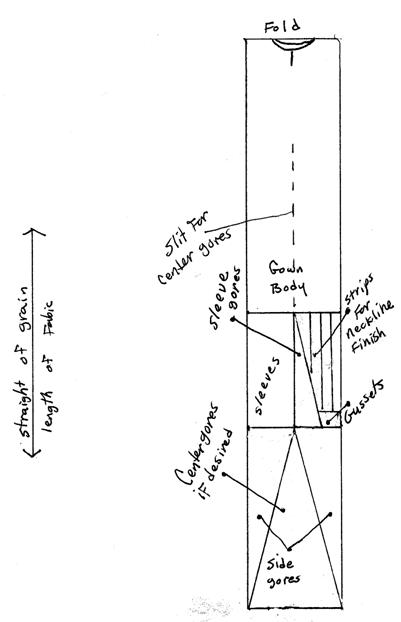

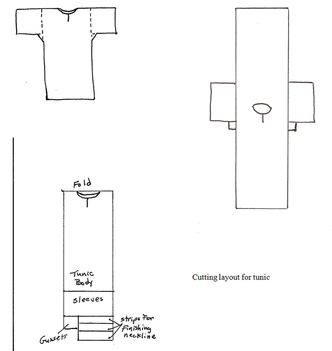

- Patterns varied; see basic gown pattern in hand-out for chemise; and basic tunic for shirt, but with long tapering sleeves

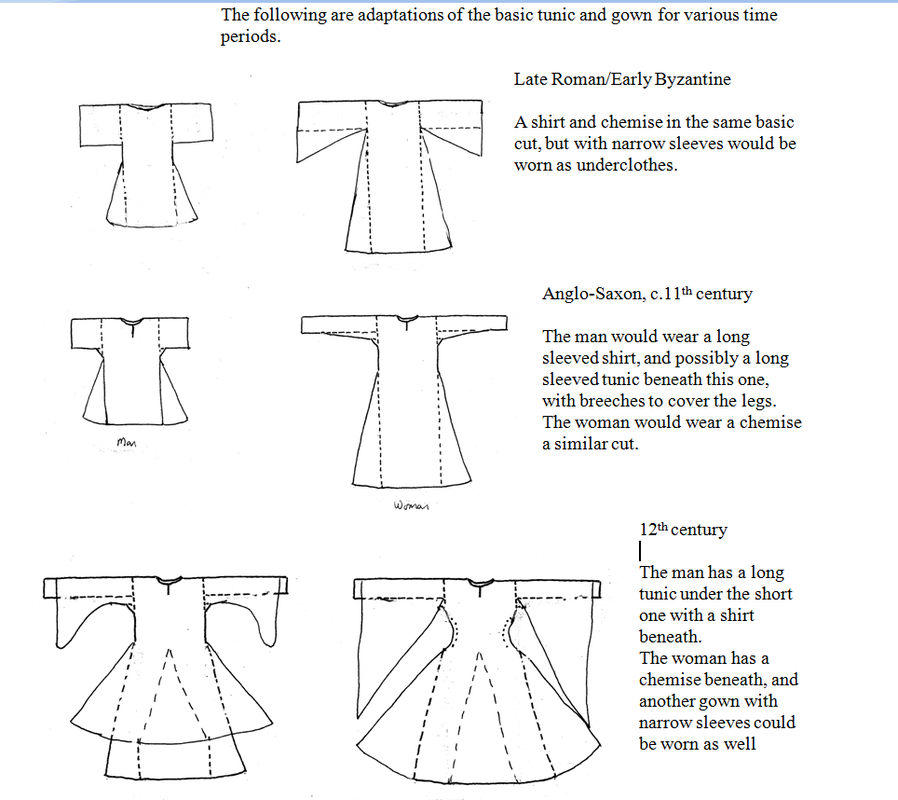

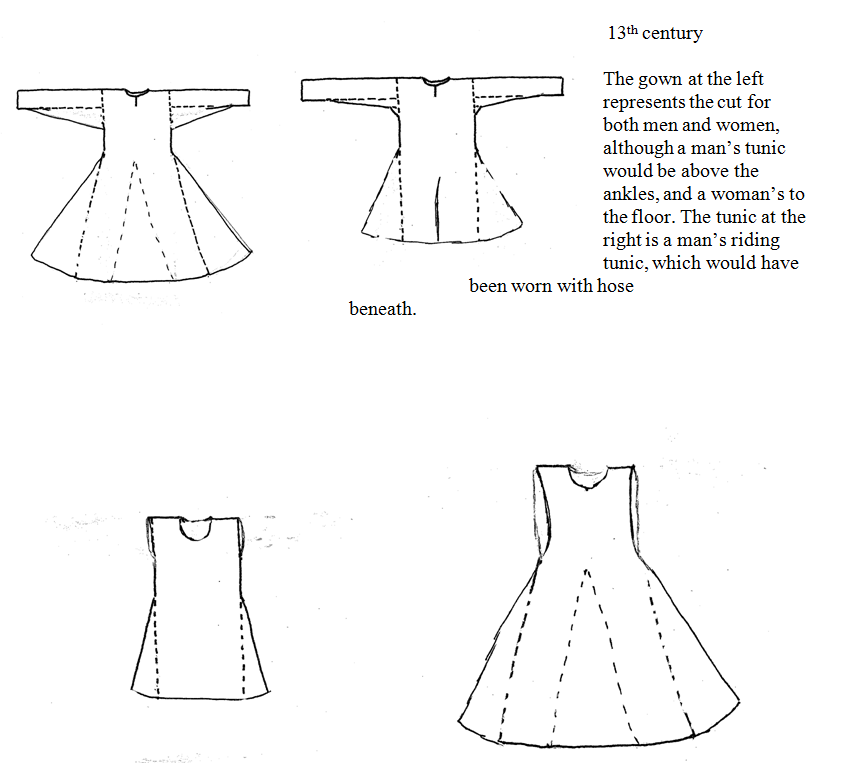

- Overgarments—differ according to period and preference—more than one style of garment existed in any given period. See hand-out.

- Layout of pattern—conserving fabric was always a goal. See hand-out.

- Undergarments

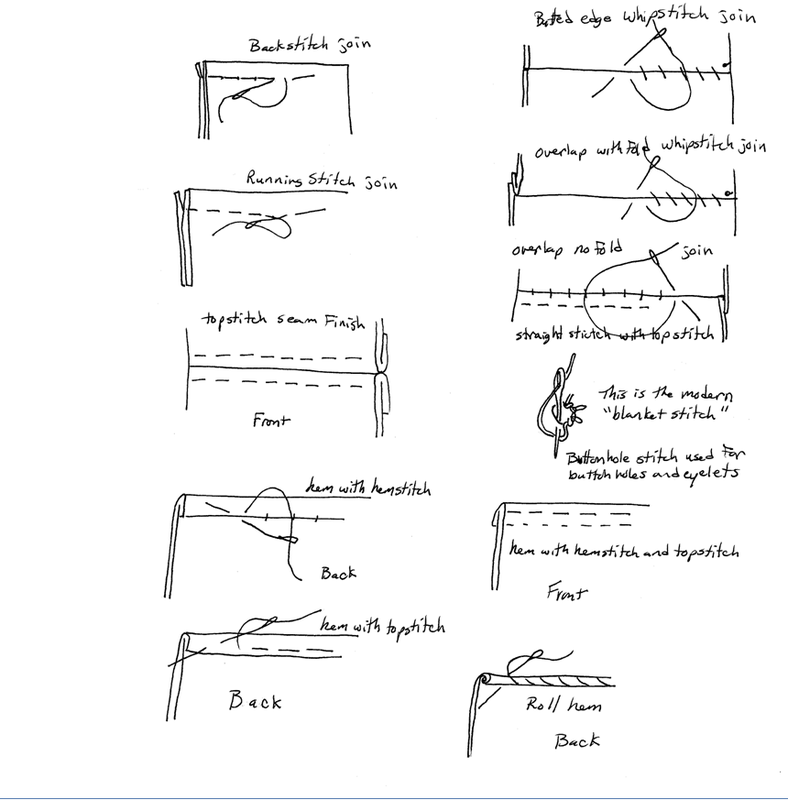

- Construction—see hand-out

- Leather and fur are usually joined by butting the edges together

- Woven fabrics are usually joined by putting the right sides of the fabric together, and sewing them together close to the edge, usually about ½ inch—this is called the seam allowance. When opened up, the edges of the fabric are on the inside.

- Seams are sewn with either a backstitch or a running stitch. The backstitch is more secure.

- Seams are generally finished—this means that you do something with the raw edges of the fabric along the seam allowances inside the garment.

- Topstitching them to the garment is most common. The edges may be left raw, or turned under like a hem if it doesn’t add too much bulk to the seam.

- Pinking: pinking in period was usually used for decorative applications, but there is some documentation for pinked seam edges.

- Seams are finished for several reasons

- It makes the seam lie flat.

- It helps support the weight of the garment.

- It helps keep the raw edges from raveling

- Hemming: there are several ways of hemming—see hand-out

- Facings

- Used for necklines, and openings where buttons or lacing will be used to close the garment

- Strip facings—most common

- A strip of fabric—not necessary the same type as the garment, is sewn along the edge to be faced (right sides together), then turned to the inside of the garment and stitched in place.

- This is similar to modern bias tape facings. However there is no evidence that period strip facings were cut on the bias. There were made from leftover pieces, which were saved for this use.

- Shaped facings

- Shaped facings are cut identically to the place in the garment where they will attach, but are only a few inches wide. These are easier to sew in as they are shaped like the garment.

- These were commonly seen in areas that needed extra reinforcement, especially where buttonholes or eyelets will be placed. The added layer of the facing keeps the fabric from stretching or tearing

- Hems can be used instead of facing on straight edges. A roll hems can be used on very thin fabric even if the edge is highly curved.

- Closures

- Neck slit—a brooch would be used to close the slit at the top

- Lacing

- A seam is left open and finished. The eyelets are sewn along both sides of the opening, and a lace is used to close the garment. See hand-out.

- Grommets were not used in fabric in period. They damage the fabric. Period examples of grommets were all used in leather.

- Buttons

- Unlike modern buttons, there is no overlap. The buttons were sewn to the very edge of the garment with a thread shank. The buttonholes were placed close to the opposite edge. This system makes an overlap unnecessary.

- Button loops: with the exception of toggle buttons used on shoes or in some early period cultures, thread loops were probably not used on period European clothes.

- Drawstrings

- Used for drawers and pants

- Used to gather the necklines of shirts and chemises in some periods and styles.

- Points

- Points are a type of lacing system that uses short pieces of lace in several places to hold a garment together.

- In later period it is used to attach sleeves to the garment and to attach breeches to doublet, and codpiece to breeches.

- In earlier periods this was used to attach a man’s hose to his drawers, or to a belt to hold them up.

- Hooks and eyes

- Some evidence in very late periods

- Large versions were found as cloak closures, belt buckles, etc.

- Zippers, snaps, elastic, and velcro did not exist in period

- Hands on practice with sewing

Patterns

Basic Tunic

Early 14th century surcoats

Surcoats were worn over the other garments as the name suggests. The short one at the left is a man’s surcoat, and the long, full one to the right is a woman’s.

Surcoats were worn over the other garments as the name suggests. The short one at the left is a man’s surcoat, and the long, full one to the right is a woman’s.

Basic hand stitches found in period.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Textiles and Clothing: Medieval Finds from Excavations in London c. 1150-1450, Elisabeth Crowfoot, Frances Pritchard, and Kay Staniland; Museum of London, 1992

Tailor’s Pattern Book, 1589, Juan de Alcega (facsimile), Jean Pain and Cecilia Bainton, trans.; Costume and Fashion Press, 1999

Cut My Cote, Dorothy K. Burnham; Royal Ontario Museum, 1973

The Medieval Tailor’s Assistant: Making Common Garments 1200-1500, Sarah Thursfield; Costume and Fashion Press, 2001

Textiles and Clothing: Medieval Finds from Excavations in London c. 1150-1450, Elisabeth Crowfoot, Frances Pritchard, and Kay Staniland; Museum of London, 1992

Tailor’s Pattern Book, 1589, Juan de Alcega (facsimile), Jean Pain and Cecilia Bainton, trans.; Costume and Fashion Press, 1999

Cut My Cote, Dorothy K. Burnham; Royal Ontario Museum, 1973

The Medieval Tailor’s Assistant: Making Common Garments 1200-1500, Sarah Thursfield; Costume and Fashion Press, 2001