The Bliaut Revisted

I have been researching the garment known as the bliaut since 1980.[1] It has been both a joy and a frustration. I do not claim to have the definitive answer about what the bliaut is, but I believe I can describe a few things that it is not, and also provide guidance and possible patterns that are, I believe, close to the garments worn in period. As with most garments, both modern and historical, there is more than one way to get there. This is mine. My definition of the bliaut for the purposes of this class is: a garment of the nobility in the late 11th and at least first half of the the 12th centuries, worn by both women and men. It was generally made of silk and embellished with embroidery around a keyhole neck, was snug through the upper body, and had full skirts that fell into folds from the hip.

Before we look at what I think is right, I believe it is useful to talk about where earlier concepts went wrong and why. There are two main sources that led us astray. Writings from the early part of the 20th century, and the visual depictions of these garments in the statuary on Chartres Cathedral.

There are two main references, both written in the 1920s, that are the source of much of the erroneous information that was repeated in later writings. These are Costume and Fashion, Vol. 2 by Herbert Norris and Women's Costume in French Texts of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries by Eunice Rathbone Goddard.

Norris went through unbelievable machinations to figure out how to make these garments so that they would look exactly like the statuary at Chartres. He held that the men's garments had separate skirts, (p. 32) and the women's did not, but instead had broomstick pleated, and had smocking. (p. 40) The men's garments were made tight by some kind of hook in the back. (pp. 31-32) He gave us the "oriental surcoat" (pp. 42-43), which was a misinterpretation of a mantle, as well as the wide corset like belt (p. 41), and the "corsage"--a bizarre quilted garment resembling an armored gambeson (p. 40). And he said women wore corsets (p. 37). Unfortunately, these pronouncements were accepted as true despite his lack of cited sources, because there was so little information about medieval costume in general for many years following his book. Several later costume books copied these ideas in part or in whole.[2]

Ms. Goddard may have been the original source for the belief that women's bliauts had a separate skirt. Had she let the 12th century romantic lays speak for themselves, we might never have had a problem, but she had an introduction in which she made numerous statements that have no basis in fact. She claimed that the bliaut had separate skirts for two reasons: First because the garment is described as having a cors, which she defines as bodice, and a gironee, which she describes as a skirt. Of course, just because the top and bottom of a garment described separately does not necessarily indicate that there were actually two separate pieces.

Further, I would argue from my own translation that cors refers to the main part of the garment--the "body", and that gironee describes the way that the skirt is made full by the use of gores. The term "gyronny" in heraldry describes a field made up of triangles[3], much as gores, triangular pieces of cloth, make a skirt full. I think the heraldic term ans the skirt technique are linked, but it is a "chicken or the egg"-type question as to which came first. I have not seen this opinion expressed by any written source, so it is mine alone. This technique for making a skirt was used both before and after the 12th C, further evidence that a separate skirt was unlikely: A totally new way of patterning does not come into existance and then vanish for another 300 years.

Professor Goddard refers to the skirts as being made full by the use of gores and wonders at the lack of a contemporary term for "gore" (22). I believe that gironee or giron is that term, but that it refers to the gored skirt technique rather than an individual piece. Another reason for stating that the skirt was a separate piece is based on an extant garment, that she calls the "Vienna bliaut," after the caption accompanying a detailed drawing of which appears in Histoire du Costume en France Depuis les 18e Siecle (Paris 1875), page 148 by Jules Quichérat, a well known French historian and archeologist of the 19th century. This drawing came from an earlier German work.[4]

This garment does not meet my definition of a bliaut, nor that of most modern costumers. His definition of the bliaut is a garment made full by the use of gores and pleats, which was first introduced by the Normans who had been on crusade. (147) The drawing is a man's garment, clearly made for a person of some note, as the garment is silk, and the date and place of manufacture, Palermo in 1181 CE, is woven into the silk brocade trim, which has inscriptions in Latin and Arabic (Quichérat, 148). It is approximately knee length, has sleeves that taper to a snug wrist, and brocaded bands on the hem and cuffs. The neck opening is not the keyhole type, but has the opening slit to the left side, which is trimmed with a narrow band of trim. This side opening is similar to other known garments from Germany and Eastern Europe, a drawing of which appears on page 139 of the Quichérat book. There is no embroidery on the garment, the sleeves are unlike those depicted on bliauts, except as undersleeves, throughout Western Europe, and there are pleats on the upper body of the garment. It has a side, rather than front slit, and the garment is quite full through the body, rather than the slimmer profile of the bliaut. What is most confusing is that there is clearly no separate skirt, as Professor Goddard states, as the gores in the skirt extend well above the waistline.

Shortly after referring to this garment in her book, Professor Goddard makes several other astonishing claims that appear to refer to this garment, but cannot.The drawing itself does not support her interpretations. She talks about trim on the upper arm concealing a seam, "elastic jersey like materials," and the necessity of having to sew or lace the garment sleeves on with each wearing because they were so snug at the wrist. (20-21) I have no idea where these ideas may have come from; I wonder whether in her researches she had been looking at more than one illustration and failed to properly reference the others. She also states that "illustrations of the period" show that there was a separate skirt (51), though the single manuscript example she gives, I believe, depicts the skirt pulled up and draped over a belt. This was both a common practice, and it is found in numerous manuscript paintings. It could also be a belt, but her description of a separate skirt sewn in "sometimes with another bias piece to insure a better fit around the hips" (51) makes no sense. I have found no illustrations that indicate a separate skirt either in manuscripts, carvings, or statues.

Our last source of misunderstanding comes from trying to interpret period depictions of the garments from the sculptures on Chartres Cathedral. There is no reason to believe that statues made at the time, when realistic portraiture was not an important factor in Western art, would realistically depict details of the costumes worn in that time. Also, it is clear that the sculptures purposefully have an architectural character to compliment the building, the columns, and other features. [5] In some figures, the drapery is exaggerated, has an abundance of zigzags, and other features intended to convey movement, or some other aspect of the figure. [6] Parts of the body are often indicated by curves in the drapery.[7] Further, the stained glass at Chartres, depicts the garments in an entirely different way, and is more consistent with manuscript paintings of the period.[8] Other factors to consider are whether or not the craftsmen actually had any idea what the clothing looked like, except perhaps from a distance, technical limitations imposed by the stone-working tools available, and the nonrepresentational nature of Western art in general at the time.[9] That is not to say that we should distrust every single feature of the visual depictions left to us. Basic shapes and decoration that are similar over time and location, are far more trustworthy than a single sculpture. The depiction of sleeve shapes, mantles, and embroidered necklines are very consistent in 12th century art and architecture.

There are better sources from this period. Some of the best are the writings of the period that describe the costumes in a realistic way. The best of those are the romantic lays, verses used to entertain the nobility, and written by people who had the opportunity to actually see the garments themselves close up. The lays were particularly popular with women, who would know firsthand if the descriptions were correct or not. The Song of Roland, or La Chanson de Roland, may be the earliest written work to use the word bliaut ("blialt" verse XX, line 9), a final version of which is believed to have appeared at the end of the 11th century.[10] In that work, the Roland is described as wearing a bliaut beneath his armor, which is consistent with the romances.

An excellent source for descriptions of the lays is Monica Wright's book, Weaving Narrative: Clothing in 12th Century French Romance. She addresses the interest shown in clothing, and how specific articles of clothing, the bliaut and the mantle being two of these, help to identify the class of the characters. [11] In these works, the entire outfit was described as the "robe," the undergarment next to the skin as a "chemise," and the outer garment the "bliaut."[12] The cut and shape of the garments did not differ greatly between the classes, the differences were in the details; quality and amount of the cloth, the decoration, and the jewelry.[13] Hanging sleeves and cloaks with trailing hems became fashionable for women--both condemned by the clergy.[14] The snugness of the upper body was achieved by side lacing, though this may not have been needed or desired by everyone who wore one.[15]

Improvements to the loom, with the introduction of the horizontal treadle loom, as well as more common use of spinning wheels, meant that fine fabrics were being made in larger quantities.[16] The nobility had access to fine wools from Flanders, silk and cotton from Italy and Muslim Spain[17] as well as from Byzantium[18] and its environs, and silk and silk brocades from Sicily.[19] They also imported furs from Russia and the Baltic States to line their cloaks, called "chapes," or "chausables."[20] Clothes in the romantic lays are often described as embroidered in silk and gold and trimmed in ermine. [21] Sumptuary laws are believed to have started in Europe in the 12th century, controlling fabrics, trimmings, furs, and the "mantiel" or mantle, a garment that could only be worn by nobles.[22]

Fashion does not exist in a vacuum. Clothing styles in general do not appear out of nowhere. Most styles either evolve from what came before, are influenced by an outside source, or both. If you look at the extant Coptic 4th century shirt[23] and compare it to a 19th century Middle-Eastern folk garment, known as the Bethany dress,[24] you will immediately notice the similarities despite the passage of time. The bliaut, as previously mentioned, may have been driven by new rich fabrics used to make garments similar in pattern to those of the previous era. They may also have picked up styles from the Middle-East, including Byzantium during the first two crusades. It would have been surprising if they had not. By 1130 C.E. the Middle-East was full of Crusader States, founded during the First Crusade.[25] Byzantine art of the 10th-11th century shows hanging sleeves of the bliaut type in a number of works,[26] and this may have been the source for the exaggerated sleeve of the bliaut. We know many of the fabrics came from the Middle-East, and that other things did as well. Byzantine jewelry had been prized even before the crusades, and continued to have an influence on Western styles.[27] Also, European merchants began dealing directly with merchants in both the near and far East as the sea route to China was opened.[28]

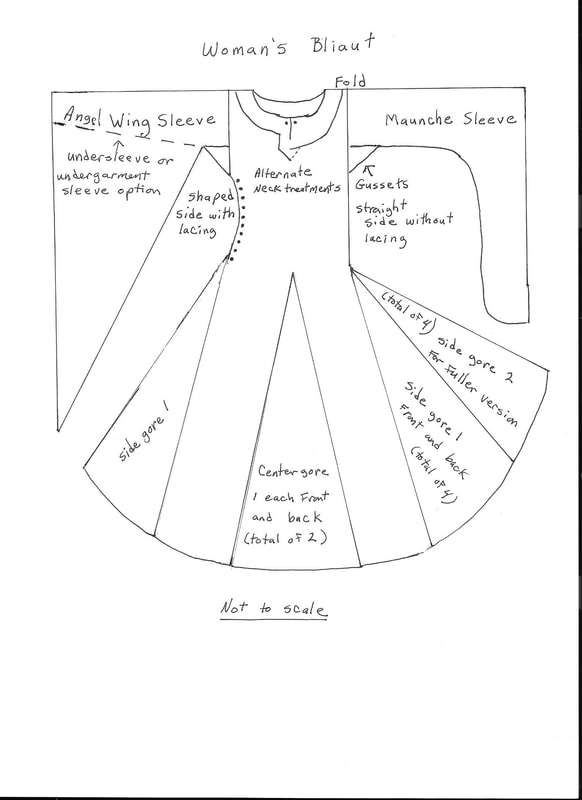

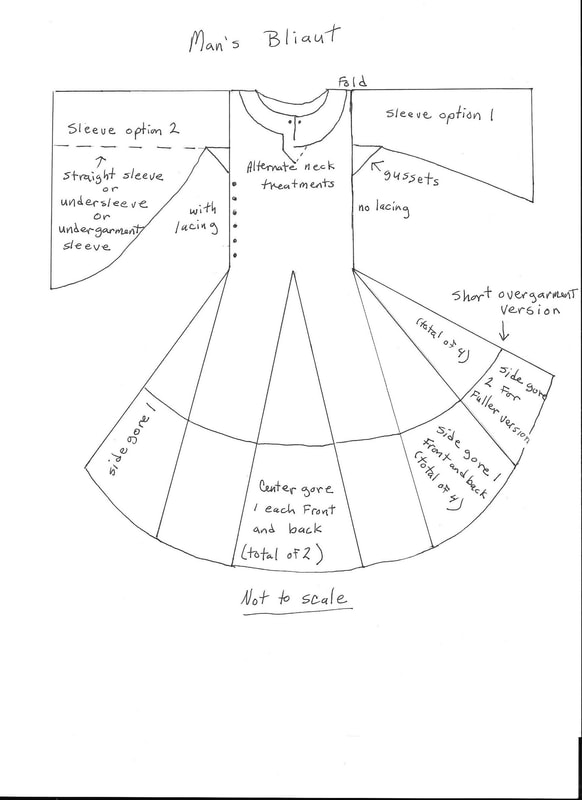

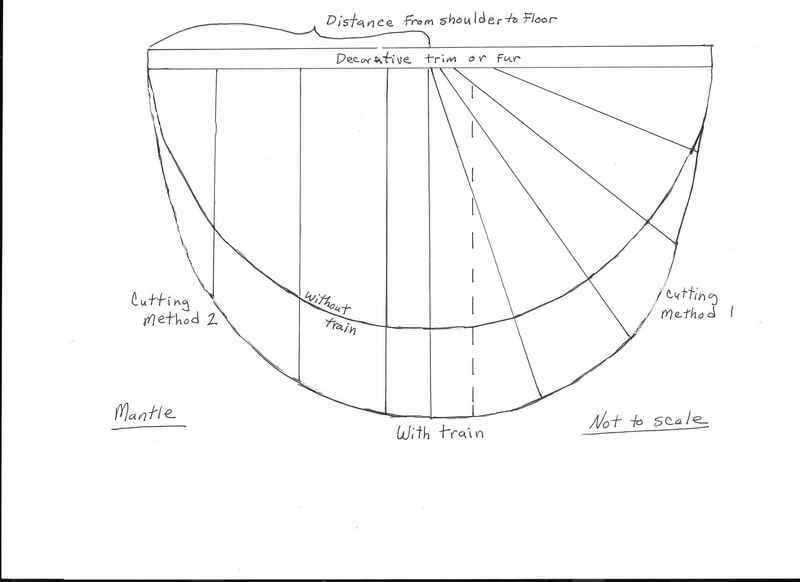

Here is what I think about the construction and detail of these garments, based on the research here, as well as looking at thousands of images in different mediums over the last thirty-six years. I believe that they were very similar to those that came before, full skirted with multiple gores, one each front and back, and at least one in each side, perhaps as many as three, depending on the width of the fabric and the desired fullness. On a woman, the front gore should stop at the navel, the side gores at the tops of the hips, and the back, at the top of the butt. On men, it will be more individual depending on their figure. The sleeves were long, hanging outer sleeves, either of the "maunche" type[29] or what we would call an "angel wing sleeve." As set in sleeves were not yet used, there would be a gusset in the underarm. I do not think the sleeves were lined, as the extra weight, even of fine silk, would have pulled at the shoulders and thrown off the line of the garment. The garment was snug through the torso, often made very snug with side lacing. The torso would be cut straight, or with a gentle curve to accommodate the figure of the person who would wear it, and how snug they wished it to be. They would have elaborate embroidery at the neck in silk, silver, and gold.[30] Examples from extant pouches show silk embroidery with stem stitch and silver-gilt thread in underside couching.[31] The neck was of the keyhole type with a front slit, held together at the top with a brooch.[32] Eyelets may have been worked into the embroidery to keep a brooch from tearing it over time. They were worn over a light weight linen chemise, and perhaps another undergarment with snug sleeves, and probably narrower skirts, depending on the weather. There are numerous depictions of men's bliauts where the outer garment has a knee length skirt over an undergarment with a long skirt that is less full. It is also possible that there were false undersleeves attached to the outer sleeves at the top in the bliauts of both sexes. As accessories, the women wore double wrapped belts, probably tablet woven in silk thread, large oval fine silk veils, and dressed their hair in two plaits, braided with ribbon, that hung to the front. False hair was likely used where a woman had insufficient of her own. Men's accessories would have included a narrow leather belt and probably a pouch, also embroidered richly. Both would have worn a mantle, a large half circle, probably made up of gores, of silk or fine wool, lined in silk or fine fur. There may have been a decorative band of fur or embroidery along the front edge. It would have been closed with an elaborate large brooch, or silk ties that passed through eyelets.

Keep in mind, that these are the garments of the nobility. There is no such thing as a middle-class bliaut. The middle classes would not have the same quality of fabric, the hanging sleeves, the embroidery, the jewelry, or the mantle. They would have had a garment of similar cut, not so tight, made out of wool, worn over a heavier linen chemise.

I have included no period images here because there is no single, or even small group of images, that I believe are definitive. As I said earlier, this is only my way. I'm sure others can look at the evidence and come to other conclusions. I hope this inspires people to do their own research, and challenge me on my conclusions.

[1] And I ask you all to forgive me for my article in Tournaments Illuminated No. 83 (1987), The Bliaut: A New Perspective on Pattern and Cut, pg. 15. I was terribly wrong, even if I was starting to look in the right places.

[2] The Holkeboer book is one.

[3] Fox-Davies 93-94

[4] Bock, hie Kleinodien des heil raemischen Reichies deutscher Nation.

[5] Stoddard p. 13

[6] Ibid. PP. 20-21

[7] Ibid. p. 51

[8] Personal observations from Miller

[9] A New Approach to the Bliaut class

[10] La Chanson de Roland, verse XX, line 9 in the original poem.

[11] Wright, p. 41

[12] Ibid. p. 24

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid p. 25

[15] Ibid 26

[16] Ibid. p. 28

[17] Ibid p. 27

[18] Wright p. 31, The Glory of Byzantium p. 9

[19] Wright p. 32, Scott, pp. 154-155

[20] Wright pp. 24, 31

[21] Ibid. pp.48-49

[22] Ibid. pp. 38, 49

[23] Burnham p. 9

[24] Folkwear pattern 01

[25] McEvedy p. 64

[26] The Glory of Byzantium p. 467, for example

[27] Tait p. 138

[28] Wild, The Silk Road class

[29] Yes, another heraldic reference. Fox-Davies, pp. 222-223

[30] The embroidery was probably done on a separate piece of fabric, most likely linen, and applied to the neckline. This would allow the embroidery to be removed to another garment when this one no longer suited.

[31] King and Levey, pp. 21, 33

[32] Eyelets may have been worked into the embroidery to keep a brooch from tearing it over time.

Before we look at what I think is right, I believe it is useful to talk about where earlier concepts went wrong and why. There are two main sources that led us astray. Writings from the early part of the 20th century, and the visual depictions of these garments in the statuary on Chartres Cathedral.

There are two main references, both written in the 1920s, that are the source of much of the erroneous information that was repeated in later writings. These are Costume and Fashion, Vol. 2 by Herbert Norris and Women's Costume in French Texts of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries by Eunice Rathbone Goddard.

Norris went through unbelievable machinations to figure out how to make these garments so that they would look exactly like the statuary at Chartres. He held that the men's garments had separate skirts, (p. 32) and the women's did not, but instead had broomstick pleated, and had smocking. (p. 40) The men's garments were made tight by some kind of hook in the back. (pp. 31-32) He gave us the "oriental surcoat" (pp. 42-43), which was a misinterpretation of a mantle, as well as the wide corset like belt (p. 41), and the "corsage"--a bizarre quilted garment resembling an armored gambeson (p. 40). And he said women wore corsets (p. 37). Unfortunately, these pronouncements were accepted as true despite his lack of cited sources, because there was so little information about medieval costume in general for many years following his book. Several later costume books copied these ideas in part or in whole.[2]

Ms. Goddard may have been the original source for the belief that women's bliauts had a separate skirt. Had she let the 12th century romantic lays speak for themselves, we might never have had a problem, but she had an introduction in which she made numerous statements that have no basis in fact. She claimed that the bliaut had separate skirts for two reasons: First because the garment is described as having a cors, which she defines as bodice, and a gironee, which she describes as a skirt. Of course, just because the top and bottom of a garment described separately does not necessarily indicate that there were actually two separate pieces.

Further, I would argue from my own translation that cors refers to the main part of the garment--the "body", and that gironee describes the way that the skirt is made full by the use of gores. The term "gyronny" in heraldry describes a field made up of triangles[3], much as gores, triangular pieces of cloth, make a skirt full. I think the heraldic term ans the skirt technique are linked, but it is a "chicken or the egg"-type question as to which came first. I have not seen this opinion expressed by any written source, so it is mine alone. This technique for making a skirt was used both before and after the 12th C, further evidence that a separate skirt was unlikely: A totally new way of patterning does not come into existance and then vanish for another 300 years.

Professor Goddard refers to the skirts as being made full by the use of gores and wonders at the lack of a contemporary term for "gore" (22). I believe that gironee or giron is that term, but that it refers to the gored skirt technique rather than an individual piece. Another reason for stating that the skirt was a separate piece is based on an extant garment, that she calls the "Vienna bliaut," after the caption accompanying a detailed drawing of which appears in Histoire du Costume en France Depuis les 18e Siecle (Paris 1875), page 148 by Jules Quichérat, a well known French historian and archeologist of the 19th century. This drawing came from an earlier German work.[4]

This garment does not meet my definition of a bliaut, nor that of most modern costumers. His definition of the bliaut is a garment made full by the use of gores and pleats, which was first introduced by the Normans who had been on crusade. (147) The drawing is a man's garment, clearly made for a person of some note, as the garment is silk, and the date and place of manufacture, Palermo in 1181 CE, is woven into the silk brocade trim, which has inscriptions in Latin and Arabic (Quichérat, 148). It is approximately knee length, has sleeves that taper to a snug wrist, and brocaded bands on the hem and cuffs. The neck opening is not the keyhole type, but has the opening slit to the left side, which is trimmed with a narrow band of trim. This side opening is similar to other known garments from Germany and Eastern Europe, a drawing of which appears on page 139 of the Quichérat book. There is no embroidery on the garment, the sleeves are unlike those depicted on bliauts, except as undersleeves, throughout Western Europe, and there are pleats on the upper body of the garment. It has a side, rather than front slit, and the garment is quite full through the body, rather than the slimmer profile of the bliaut. What is most confusing is that there is clearly no separate skirt, as Professor Goddard states, as the gores in the skirt extend well above the waistline.

Shortly after referring to this garment in her book, Professor Goddard makes several other astonishing claims that appear to refer to this garment, but cannot.The drawing itself does not support her interpretations. She talks about trim on the upper arm concealing a seam, "elastic jersey like materials," and the necessity of having to sew or lace the garment sleeves on with each wearing because they were so snug at the wrist. (20-21) I have no idea where these ideas may have come from; I wonder whether in her researches she had been looking at more than one illustration and failed to properly reference the others. She also states that "illustrations of the period" show that there was a separate skirt (51), though the single manuscript example she gives, I believe, depicts the skirt pulled up and draped over a belt. This was both a common practice, and it is found in numerous manuscript paintings. It could also be a belt, but her description of a separate skirt sewn in "sometimes with another bias piece to insure a better fit around the hips" (51) makes no sense. I have found no illustrations that indicate a separate skirt either in manuscripts, carvings, or statues.

Our last source of misunderstanding comes from trying to interpret period depictions of the garments from the sculptures on Chartres Cathedral. There is no reason to believe that statues made at the time, when realistic portraiture was not an important factor in Western art, would realistically depict details of the costumes worn in that time. Also, it is clear that the sculptures purposefully have an architectural character to compliment the building, the columns, and other features. [5] In some figures, the drapery is exaggerated, has an abundance of zigzags, and other features intended to convey movement, or some other aspect of the figure. [6] Parts of the body are often indicated by curves in the drapery.[7] Further, the stained glass at Chartres, depicts the garments in an entirely different way, and is more consistent with manuscript paintings of the period.[8] Other factors to consider are whether or not the craftsmen actually had any idea what the clothing looked like, except perhaps from a distance, technical limitations imposed by the stone-working tools available, and the nonrepresentational nature of Western art in general at the time.[9] That is not to say that we should distrust every single feature of the visual depictions left to us. Basic shapes and decoration that are similar over time and location, are far more trustworthy than a single sculpture. The depiction of sleeve shapes, mantles, and embroidered necklines are very consistent in 12th century art and architecture.

There are better sources from this period. Some of the best are the writings of the period that describe the costumes in a realistic way. The best of those are the romantic lays, verses used to entertain the nobility, and written by people who had the opportunity to actually see the garments themselves close up. The lays were particularly popular with women, who would know firsthand if the descriptions were correct or not. The Song of Roland, or La Chanson de Roland, may be the earliest written work to use the word bliaut ("blialt" verse XX, line 9), a final version of which is believed to have appeared at the end of the 11th century.[10] In that work, the Roland is described as wearing a bliaut beneath his armor, which is consistent with the romances.

An excellent source for descriptions of the lays is Monica Wright's book, Weaving Narrative: Clothing in 12th Century French Romance. She addresses the interest shown in clothing, and how specific articles of clothing, the bliaut and the mantle being two of these, help to identify the class of the characters. [11] In these works, the entire outfit was described as the "robe," the undergarment next to the skin as a "chemise," and the outer garment the "bliaut."[12] The cut and shape of the garments did not differ greatly between the classes, the differences were in the details; quality and amount of the cloth, the decoration, and the jewelry.[13] Hanging sleeves and cloaks with trailing hems became fashionable for women--both condemned by the clergy.[14] The snugness of the upper body was achieved by side lacing, though this may not have been needed or desired by everyone who wore one.[15]

Improvements to the loom, with the introduction of the horizontal treadle loom, as well as more common use of spinning wheels, meant that fine fabrics were being made in larger quantities.[16] The nobility had access to fine wools from Flanders, silk and cotton from Italy and Muslim Spain[17] as well as from Byzantium[18] and its environs, and silk and silk brocades from Sicily.[19] They also imported furs from Russia and the Baltic States to line their cloaks, called "chapes," or "chausables."[20] Clothes in the romantic lays are often described as embroidered in silk and gold and trimmed in ermine. [21] Sumptuary laws are believed to have started in Europe in the 12th century, controlling fabrics, trimmings, furs, and the "mantiel" or mantle, a garment that could only be worn by nobles.[22]

Fashion does not exist in a vacuum. Clothing styles in general do not appear out of nowhere. Most styles either evolve from what came before, are influenced by an outside source, or both. If you look at the extant Coptic 4th century shirt[23] and compare it to a 19th century Middle-Eastern folk garment, known as the Bethany dress,[24] you will immediately notice the similarities despite the passage of time. The bliaut, as previously mentioned, may have been driven by new rich fabrics used to make garments similar in pattern to those of the previous era. They may also have picked up styles from the Middle-East, including Byzantium during the first two crusades. It would have been surprising if they had not. By 1130 C.E. the Middle-East was full of Crusader States, founded during the First Crusade.[25] Byzantine art of the 10th-11th century shows hanging sleeves of the bliaut type in a number of works,[26] and this may have been the source for the exaggerated sleeve of the bliaut. We know many of the fabrics came from the Middle-East, and that other things did as well. Byzantine jewelry had been prized even before the crusades, and continued to have an influence on Western styles.[27] Also, European merchants began dealing directly with merchants in both the near and far East as the sea route to China was opened.[28]

Here is what I think about the construction and detail of these garments, based on the research here, as well as looking at thousands of images in different mediums over the last thirty-six years. I believe that they were very similar to those that came before, full skirted with multiple gores, one each front and back, and at least one in each side, perhaps as many as three, depending on the width of the fabric and the desired fullness. On a woman, the front gore should stop at the navel, the side gores at the tops of the hips, and the back, at the top of the butt. On men, it will be more individual depending on their figure. The sleeves were long, hanging outer sleeves, either of the "maunche" type[29] or what we would call an "angel wing sleeve." As set in sleeves were not yet used, there would be a gusset in the underarm. I do not think the sleeves were lined, as the extra weight, even of fine silk, would have pulled at the shoulders and thrown off the line of the garment. The garment was snug through the torso, often made very snug with side lacing. The torso would be cut straight, or with a gentle curve to accommodate the figure of the person who would wear it, and how snug they wished it to be. They would have elaborate embroidery at the neck in silk, silver, and gold.[30] Examples from extant pouches show silk embroidery with stem stitch and silver-gilt thread in underside couching.[31] The neck was of the keyhole type with a front slit, held together at the top with a brooch.[32] Eyelets may have been worked into the embroidery to keep a brooch from tearing it over time. They were worn over a light weight linen chemise, and perhaps another undergarment with snug sleeves, and probably narrower skirts, depending on the weather. There are numerous depictions of men's bliauts where the outer garment has a knee length skirt over an undergarment with a long skirt that is less full. It is also possible that there were false undersleeves attached to the outer sleeves at the top in the bliauts of both sexes. As accessories, the women wore double wrapped belts, probably tablet woven in silk thread, large oval fine silk veils, and dressed their hair in two plaits, braided with ribbon, that hung to the front. False hair was likely used where a woman had insufficient of her own. Men's accessories would have included a narrow leather belt and probably a pouch, also embroidered richly. Both would have worn a mantle, a large half circle, probably made up of gores, of silk or fine wool, lined in silk or fine fur. There may have been a decorative band of fur or embroidery along the front edge. It would have been closed with an elaborate large brooch, or silk ties that passed through eyelets.

Keep in mind, that these are the garments of the nobility. There is no such thing as a middle-class bliaut. The middle classes would not have the same quality of fabric, the hanging sleeves, the embroidery, the jewelry, or the mantle. They would have had a garment of similar cut, not so tight, made out of wool, worn over a heavier linen chemise.

I have included no period images here because there is no single, or even small group of images, that I believe are definitive. As I said earlier, this is only my way. I'm sure others can look at the evidence and come to other conclusions. I hope this inspires people to do their own research, and challenge me on my conclusions.

[1] And I ask you all to forgive me for my article in Tournaments Illuminated No. 83 (1987), The Bliaut: A New Perspective on Pattern and Cut, pg. 15. I was terribly wrong, even if I was starting to look in the right places.

[2] The Holkeboer book is one.

[3] Fox-Davies 93-94

[4] Bock, hie Kleinodien des heil raemischen Reichies deutscher Nation.

[5] Stoddard p. 13

[6] Ibid. PP. 20-21

[7] Ibid. p. 51

[8] Personal observations from Miller

[9] A New Approach to the Bliaut class

[10] La Chanson de Roland, verse XX, line 9 in the original poem.

[11] Wright, p. 41

[12] Ibid. p. 24

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid p. 25

[15] Ibid 26

[16] Ibid. p. 28

[17] Ibid p. 27

[18] Wright p. 31, The Glory of Byzantium p. 9

[19] Wright p. 32, Scott, pp. 154-155

[20] Wright pp. 24, 31

[21] Ibid. pp.48-49

[22] Ibid. pp. 38, 49

[23] Burnham p. 9

[24] Folkwear pattern 01

[25] McEvedy p. 64

[26] The Glory of Byzantium p. 467, for example

[27] Tait p. 138

[28] Wild, The Silk Road class

[29] Yes, another heraldic reference. Fox-Davies, pp. 222-223

[30] The embroidery was probably done on a separate piece of fabric, most likely linen, and applied to the neckline. This would allow the embroidery to be removed to another garment when this one no longer suited.

[31] King and Levey, pp. 21, 33

[32] Eyelets may have been worked into the embroidery to keep a brooch from tearing it over time.

I have shown variations here on the two sides. Also, except of a very slim woman, the line from the outside of the should to the top of the gusset would not be a perpendicular line, but would slant towards the neckline, as most of us have larger bust lines than shoulders. This is a period method of sizing. Also, if using multiple gores, take care to cut them so that you never sew a bias edge to another bias edge.

Cutting method 1 is the more period cut, and it will sit on the shoulders much better. It will, however, take more fabric.

Bibliography

Books

The Art of Heraldry, Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, 1976 edition, Library of Congress No. 68-56481. Print

The Book of Silk, Phillippa Scott, 1993, ISBN 0-500-23662-3. Print

La Chanson de Roland, authors unknown, Micaela Burnham, trans., circa 1000-1100, Joseph Bedier edition, with translation into modern French, ISBN-13: 978282060. Kindle Edition.

Chartres Cathedral, Malcolm Miller, 1996 ed. ISBN 0-85372-792-9. Print

Costume and Fashion, Vol. 2, Herbert Norris, J. M. Dent and Sons, Ltd., 1927. Print

Histoire du Costume en France Depuis les 18e Siecle , Jules Quichérat (Paris 1875) ISBN 1005862797, 1875. Print

Cut My Cote, Dorothy K. Burnham (no known relation), 1973, ROM 972.248. 1. Print

The Victoria & Albert Museum's Textile Collection: Embroidery in Britain from 1200-1750, Donald King and Santina Levey, 1993, ISBN 1851771263. Print

The Evolution of Fashion, Margot Hamilton Hill and Peter A. Bucknell, 1987 edition, ISBN 0-89676-099-5. Print

The Glory of Byzantium, Helen C. Evans and William D. Wixom, eds., 1997, ISBN 0-87099-778-5. Print

Harrap's New Collegiate French and English Dictionary, 1998 edition, ISBN 8442 1873 4. Print

Jewelry: 7000 Years, Hugh Tait, ed., 1986, ISBN 0-8109-1157-4. Print

The "Headmaster" of Chartres and the Origins of "Gothic"Sculpture, C. Edson Armi, 1994. Print

Patterns for Theatrical Costumes, Katherine Strand Holkeboer, 1993 edition, ISBN 0-89676-125-8. Print

The Penguin Altlas of Medieval History, Colin McEvedy, 1979 edition, ISBN -0-14-0708.22-7. Print

Sculptures of the West Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Whitney S. Stoddard, 1952 and 1987 (includes two smaller books). Print

The Song of Roland, Dorothy Sayers, trans., 1978 ed. ISBN 0 14 044.075 5. Print

Weaving Narrative: Clothing in 12th Century French Romance, Monica Wright, 2009, ISBN 9780271035666. Print

Women's Costume in French Texts of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, Eunice Rathbone Goddard, The John's Hopkins Press, 1927. Print. (Also available free on-line)

Classes

The Silk Road, taught by Oliver Wild, Pennsic War 1992, http://gallery.sjsu.edu/silk road/hitory.htm. Lecture

"A New Approach to the Bliaut", taught by Arianna (no other name available), Pennsic War 1999 (This class was about the effect of architecture on the way the bliaut was depicted in statuary, especially at Chartres Cathedral.) Lecture.

Other

Folkwear Pattern 01, The Bethany Dress. Print.

Books

The Art of Heraldry, Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, 1976 edition, Library of Congress No. 68-56481. Print

The Book of Silk, Phillippa Scott, 1993, ISBN 0-500-23662-3. Print

La Chanson de Roland, authors unknown, Micaela Burnham, trans., circa 1000-1100, Joseph Bedier edition, with translation into modern French, ISBN-13: 978282060. Kindle Edition.

Chartres Cathedral, Malcolm Miller, 1996 ed. ISBN 0-85372-792-9. Print

Costume and Fashion, Vol. 2, Herbert Norris, J. M. Dent and Sons, Ltd., 1927. Print

Histoire du Costume en France Depuis les 18e Siecle , Jules Quichérat (Paris 1875) ISBN 1005862797, 1875. Print

Cut My Cote, Dorothy K. Burnham (no known relation), 1973, ROM 972.248. 1. Print

The Victoria & Albert Museum's Textile Collection: Embroidery in Britain from 1200-1750, Donald King and Santina Levey, 1993, ISBN 1851771263. Print

The Evolution of Fashion, Margot Hamilton Hill and Peter A. Bucknell, 1987 edition, ISBN 0-89676-099-5. Print

The Glory of Byzantium, Helen C. Evans and William D. Wixom, eds., 1997, ISBN 0-87099-778-5. Print

Harrap's New Collegiate French and English Dictionary, 1998 edition, ISBN 8442 1873 4. Print

Jewelry: 7000 Years, Hugh Tait, ed., 1986, ISBN 0-8109-1157-4. Print

The "Headmaster" of Chartres and the Origins of "Gothic"Sculpture, C. Edson Armi, 1994. Print

Patterns for Theatrical Costumes, Katherine Strand Holkeboer, 1993 edition, ISBN 0-89676-125-8. Print

The Penguin Altlas of Medieval History, Colin McEvedy, 1979 edition, ISBN -0-14-0708.22-7. Print

Sculptures of the West Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Whitney S. Stoddard, 1952 and 1987 (includes two smaller books). Print

The Song of Roland, Dorothy Sayers, trans., 1978 ed. ISBN 0 14 044.075 5. Print

Weaving Narrative: Clothing in 12th Century French Romance, Monica Wright, 2009, ISBN 9780271035666. Print

Women's Costume in French Texts of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, Eunice Rathbone Goddard, The John's Hopkins Press, 1927. Print. (Also available free on-line)

Classes

The Silk Road, taught by Oliver Wild, Pennsic War 1992, http://gallery.sjsu.edu/silk road/hitory.htm. Lecture

"A New Approach to the Bliaut", taught by Arianna (no other name available), Pennsic War 1999 (This class was about the effect of architecture on the way the bliaut was depicted in statuary, especially at Chartres Cathedral.) Lecture.

Other

Folkwear Pattern 01, The Bethany Dress. Print.