Unraveling the Knot: Elizabethan Gardens

Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 2002)

A “knot” was the word most often used to describe garden beds of the 16th century in England. This term is derived from the often-elaborate knotwork and interlace type designs used in the plantings and other materials that the beds contained. Francis Bacon’s famous essay Of Gardens eschews the intricate knots with, “you may see as good sights many times in tarts.”[1] But a knot didn’t have to be intricate. It could be a simple bed, divided into quarters by pathway. This was the most common type of bed, and was a primary element in the garden scheme,[2] leftover, as it was, from medieval times.[3]

The Elizabethan gardens of the wealthy involved acres of land with numerous planted beds, as well as many other elements. Some of these were benches, fountains, architectural elements such as columns, heraldic elements, topiary and clipped shrubs, potted plants of various kinds, statuary, sundials, pathways, cisterns, reflecting pools, and arbors.[4] Toward the end of the period you see these in fantastic array, as well as large elements such as terracing, bowling greens, grottos, large gazebos and pergolas, banquet halls where dining might take place, small temples, labyrinths, mounts, and groves of trees.[5]

The Elizabethan gardens had a wide variety of plants. They included both native English plants and exotic, or “outlandish,” plants from all over the world. There was also a great deal of experimentation with plants, creating hybrids in many varieties. Both useful plants, and those grown purely for the pleasure of their beauty or scent were used. Plants might be left in their natural state, or shaped, as the hedges and topiary, or espalier trees.

Garden Design

Like many trends in the Renaissance, garden designs of this period began in Italy in the 15th century. We know a great deal about these gardens from agricultural treatises, literary sources, travel journals, paintings, and architects drawings. Most of the elements found in Elizabethan gardens began in Italy and traveled to England by way of France and the Low Countries.[6] The design of these gardens was architectural in nature, and the Italian Renaissance garden ushered in the concept of landscape architecture. The main concepts involved in the design of the gardens were classical formalism, linear perspective, and geometry.[7] The recreation of the “villa” ideal of Pliny the Elder was a potent influence on the reshaping of the garden in Italy.[8] But it is also clear from the literature that creating a beautiful garden was also seen as an attempt to recreate Eden—the perfect garden of the Bible. And perfection required control over the chaos of the natural world, which explains the obsession with geometry in garden design.[9] The garden became a meeting point for science and art as people tried to create a place where they could live in harmony with themselves and nature—an earthly paradise recovered.[10]

In England in the 16th century, there was a great desire by the nobles and wealthy to acquire manor house estates in the countryside. Because these homes did not need to be defensible, as they often did in the middle ages, they could have expansive gardens. As a result, the country house became a common element of the English landscape.[11] This manor house system persisted in England for generations longer than elsewhere in Europe; well out of our period and into the Victorian. [12]

There were some design elements that were particular to the English Renaissance garden that deserve special note. The most important of these is the use of the “knot” or beds to make up the garden, whether it was a functional kitchen garden or a pleasure garden. Other elements of importance are: rectangular, cross axis gardens at the sides of the house, a large straight path near the house called a “forthright,” a “mount” or small hill from which the garden can be viewed, a bowling green, covered walkways, mazes, topiary, and architectural elements.[13] Another important feature that is distinctly English is the incorporation of the kitchen garden into the formal garden.[14] Although architectural elements were important in the English Renaissance garden, architecture itself as a design element was not introduced until out of our period, about 1620.[15]

It should also be noted that many of the grand gardens were designed with Queen Elizabeth in mind. She often made progresses throughout the country, staying with her various nobles at their estates. Because of this, her particular symbols were often incorporated into the gardens. The Tudor rose was used heraldically, and the English wild rose, or eglantine, was planted in the gardens to honor her.[16]

Some of the designers of gardens are still known. John Thorpe was an architect who planned a number of gardens.[17] The only known designer of the intricate knot shaped gardens was Thomas Trevelyon, who also designed embroidery.[18]

Garden Uses

As noted previously, kitchen gardens were often incorporated into a formal setting, though they could be separate as well. Obviously, the kitchen garden was used to provide vegetables and herbs. But even the formal gardens had plants that were used for distilling perfumes and liquors, medicines, nosegays, strewing, or making “sweet bags” and other scented items.[19] Beyond the uses of the plants were the uses of the gardens as a whole for entertaining, meditating, and as a symbol of wealth.

Al fresco dining under tents or large gazebos, as well as masques and dances were often held in the garden in summer.[20] Often the gazebos were built on the top of the mount, so that diners could enjoy the view of the garden while eating. Masques and dances could be held on the large bowling greens. Of course, the bowling greens were also used for sport. Bowling, or “bowles,” as it was known then, was very popular in 16th century England. Another fashionable sport was tennis, and bowling greens could be converted to tennis courts, or there could be separate grass courts in the garden.[21]

The pleasure gardens of England were designed to appeal to all the senses, and the benches, viewing areas, and covered walkways were set up to create an atmosphere that was relaxing and meditative.[22] Splashing water features and birds appealed to hearing, the odor of the herbs and fragrant flowers to smell, the changes from shade to sun, pleasant breezes, and cool waters appealed to feel, the taste of the fruit from the trees to taste, and of course, the beauty of the whole garden to sight.[23]

The importance of the garden as a symbol of aristocratic magnificence should not be underestimated. Elaborate gardens were a form of important conspicuous consumption. Often the arms of the owner’s ancestors up to the present were prominently displayed, showing the noble heritage. There was a great deal of competition to get and keep the best gardeners and garden designers. The first elaborate gardens in England, built by Henry VIII, were a symbol of that monarch’s power.[24]

Garden Beds

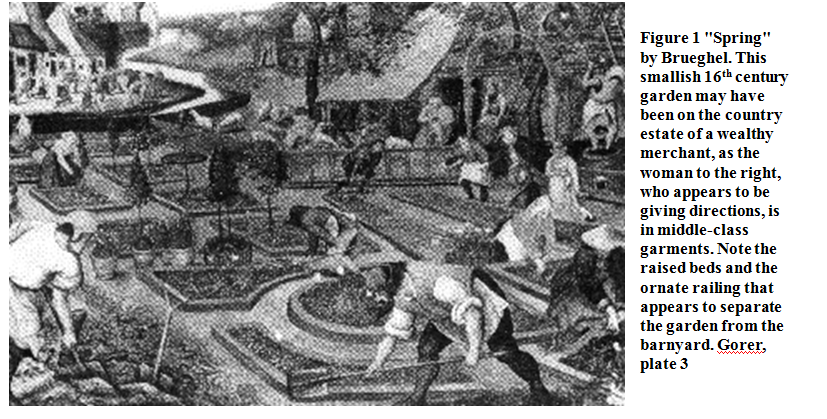

The most important element of any of these gardens was the beds themselves. The beds of this period were always raised beds. This facilitates drainage, helps separate the plants from the surrounding area, and makes the beds somewhat easier to weed and water. Often a large bed would be divided into several smaller beds, which would be separated by walkways or paths.[25] It is only the actual planted area that was raised.

The materials used to raise the beds were quite varied. They used timbers, bricks, tiles, and quarried rock.[26] The beds were usually raised only a few inches. If a plant was wanted higher than that, pots were employed. Likewise, a variety of materials were used in the beds around the plantings. Although the most common was simply black soil, red brick dust, white sand, and pebbles of a variety of colors could be used to outline or fill in the areas of knot work designs not filled by plants.[27] Some beds were planted with, or surrounded by hedge plants. Tight hedges can be shaped easily, and hedge plants often make good topiary, which was very popular in the gardens.

The division of large beds into four sections, separated by a cross shaped pathway was typical of English gardens of this period. The smaller beds might then be subdivided or not, depending on size, but the four quadrant plan was by far the most common in England, and was a holdover from medieval times. Where circular beds were employed, a large tree was usually planted in the center. In rectangular or square beds, some other type of element was usually found where the paths came together in the center.[28] Fountains were popular for large beds, topiary, sculpture, or architectural elements for smaller ones.

The pathways could be grass, rock, sand, stone, or brick. They might be covered, or be open to the sky. Arbors were used extensively, usually intermittently, but occasionally in a continuous manner. A continuous arbor was called a “pleached alley.” [29]Often benches were placed in strategic locations so that those enjoying the garden might sit and enjoy a particularly nice view. There were often borders around the beds as well. These might be plants or other materials such as lead, timbers, tiles, or even bone.

Paintings of the period often show many different kinds of flowers in a single bed, planted often in clumps with large amounts of soil showing.[30] How plants were grouped in beds would have been decided by aesthetics, the growing conditions needed, and also by astrology and alchemy as well. Kitchen gardens or herbal gardens, on the other hand, would have separated plants by type.

Garden Plants

The plants in the Elizabethan garden varied from practical to whimsical, and native to “outlandish.” Traditional plants continued to be very popular. Among these were violets, cowslips, primroses, lilies, gillyflowers, periwinkle, and all varieties of roses. Arbors could be covered with ivies or other climbing plants. Hedges were made of hawthorn, juniper, holly, elm, ilex, and box, as well as other shrubs. Thrift, germander, box, marjoram, savoury, and thyme were popular border plants.[31]

Practical plants like comfrey, rosemary, parsley, sage, and mint were also grown. Not only did these plants have use, they also provided pleasant aromas to the garden. The 16th century was the heyday of the cult of herbs, and they were cultivated for medicine, cooking, alchemy, and garden ornament.[32] Herbal medicines were prized, and most manor houses had a “stilling house” for the manufacture of them, as well as perfumes and potables.

Plants from all over the world were imported for use in English gardens as well. Some of the most popular were daffodils, hyacinths, crocus, tulips, anemones, cyclamen and many of the hellebores, particularly the “Christmas Rose.”[33] The study of botany was just coming into its own in England, and the study of botanical specimens was a popular hobby. Gerard, of herbal fame, employed William Marshall as a collector to find exotic plants from all over the world.[34] Nicholas Leate, a London merchant, traded in plants from Turkey, and also hired collectors to find new plants for him. He was also an experimenter in hybrids and grafting techniques.[35]

Plants that could not survive the winter were often grown in pots, and placed strategically throughout the garden. Citrus trees were quite often done this way, although hardy topiaries were also often grown in pots so they could be moved around as desired.

Large trees were found in groves and grottos. Pines, cypresses, laurels, elms, maples, ashes, oaks, aspens, yews, and poplars were all found in gardens. Groves of myrtle are also described in the literature.

Gardens of the Period

Many gardens that existed in this period are known, though none still exists in its original form. Because many of them were described in letters, we do have an idea of what some of them looked like.

Theobalds was modeled on and Italian plan, and it was the most Italian garden in England. It was the country garden of William Cecil. It had a moat or canal that surrounded it and a grotto. The whole garden was about seven acres in size. The “privy garden” part of it was enclosed by a wall, in the medieval style, and also had gravel walks, cherry trees, and hedges cut into various shapes. In the “great garden” there were knots gardens of various types and a large marble fountain. The surrounding canal was large enough for boating.[36]

Nonsuch, started by Henry VIII in 1538,[37] was redesigned and completed by Lord Lumley in the 1580s. He had been to Italy to view the gardens there, and he incorporated many of those elements into the garden. He planted many small groves or clumps of trees and shrubs, but the garden was still laid out in knots. He had his heraldry prominently displayed, topiary animals, marble columns and pyramids, fountains, and sculpture. But he also included less formal elements such as the “grove of Diana” that contained a grotto.[38]

Kenilworth Castle had bowers, arbors, and walkways with seats. It also boasted an aviary. The large square garden was divided into quarters with a fountain where the grass walks edged in sand intersected. There was an obelisk on each of the quarters surrounded by fragrant plants and herbs and fruit trees. There was also heraldry used as a decorative element. This was the first example in England of terracing used for viewing the gardens.[39]

Cobham Hall was finished in 1586. It was known for having for varieties of rare plants and flowers than any other garden of its time. It also had an arbor made of a living lime tree, one of the more intricate examples of espalier.[40]

Garden Manuals and Herbals

The first description of an English garden may have been in the 13th century when John de Garlande published Dictionarus.[41] The love affair with gardens in England continued, and many manuals, herbals, and other gardening books were published. In the 16th century, practical gardening manuals tended to be written for the middle class, and herbals for the aristocracy.[42] This was due to the fact that many of the authors of the herbals had aristocratic patrons. William Cecil, who owned Theobalds, was the patron of John Gerard of herbal fame, William Turner, “the father of English botany,” and Matthias de l’Obel, for whom the flower lobelia is named.[43]

John Parkinson (1567-1650) published two botanical books. Although both were published out of period, much of the material was from the 16th century. His books are Paradisi in Sole, published in 1629, and Theatrum Botanicum, published in 1640. In his books he describes many of the plants and flowers typical in Elizabethan gardens. He is credited with the creation of the flower garden as an independent type of garden.[44]

The Gardener’s Labyrinth, published in 1571 by Thomas Hill shows rectangular, square, and circular raised beds used in a garden that had a dual purpose, including both useful and purely pleasure plants. As the name suggests, maze beds were also illustrated.[45]

Francis Bacon’s essay Of Gardens, published in 1625 (but based on his earlier 1597 works) details his ideal of what an Elizabethan garden should be. Although he is not very knowledgeable about plants or gardens, he has detailed descriptions of the types of things found in them.[46]

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Published in 1499 by Francesco Colonna describes all the elements of the Italian Renaissance garden.[47]

Piero de’Crescenzi wrote Liber Ruralium Commodorum between 1304 and 1309. It is a “how to” type book, that was extremely popular, and was republished in many languages throughout our period of discussion. A 16th century edition in the British Library included miniatures depicting the various activities described in the book. This was one of the most popular manuals of the period.[48]

Another manual was The Feate of Gardening by Mayster Ion Gardener, first published in 1400 as a five-page poem. It was later transcribed into a book of miscellanies around 1440.[49]

Thomas Tusser (1515-1580) wrote a manual for the yeoman gardener that was published in 1573 called Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry. It was written in rhymed couplets.[50]

Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim (1493-1541) was a physician who wrote extensively about plants. He wrote under the name “Paracelsus” and is best know for a treatise based on the “Doctrine of Signatures,” a popular, if incorrect, theory of plants.[51]

William Turner published his first herbal in 1538, another in 1548, and his third in 1568. This latter was the first herbal to contain New World plants.[52] Turner was called the “father of English botany,”[53] and he collected dried specimens of the plants he wrote about.

The best-known herbals of the period were written by John Gerard. His Herball or Generall Histories of Plantes was published in 1597.[54]

[1] Gorer, 12

[2] Strong, 46

[3] Pregill, 232

[4] Llewellyn, 74-97

[5] Singleton, 15-16

[6] Strong, 13

[7] Pregill, 207

[8] Strong, 13

[9] Comito, 14

[10] Beretta, 38

[11] Pregill, 231

[12] Tobey, 120

[13] Tobey, 122-124

[14] Tobey, 124

[15] Strong, 15

[16] Strong, 46-47

[17] Singleton, 23

[18] Strong, 70

[19] Singleton, 4 and 54-55

[20] Strong, 11

[21] Hyams, 144

[22] Beretta, 163

[23] Beretta, 68

[24] Strong, 10

[25] Singleton, 40

[26] Gorer, 7

[27] Strong, 33

[28] Singleton, 42

[29] Singleton, 50

[30] Singleton, 42

[31] Gorer, 6

[32] Cooper, 23

[33] Singleton, 78-81; A. Coats, 112-113

[34] Singleton, 34

[35] Singleton, 36

[36] Strong, 52-53

[37] Strong, 38

[38] Strong, 63-66

[39] Strong, 50-51

[40] Strong, 69

[41] Singleton, 8

[42] Comito, 20-22

[43] Comito, 19

[44] Singleton, 31

[45] Cooper, 28

[46] Gorer, 9-10

[47] Singleton 15; Lazzoro, 21

[48] Calkins, 157-163; Hyams, 92

[49] Hyams, 95

[50] Fisher, 56-57

[51] Fisher, 40

[52] Fisher, 53-54

[53] Hyams, 144

[54] Fisher, 57-58

Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 2002)

A “knot” was the word most often used to describe garden beds of the 16th century in England. This term is derived from the often-elaborate knotwork and interlace type designs used in the plantings and other materials that the beds contained. Francis Bacon’s famous essay Of Gardens eschews the intricate knots with, “you may see as good sights many times in tarts.”[1] But a knot didn’t have to be intricate. It could be a simple bed, divided into quarters by pathway. This was the most common type of bed, and was a primary element in the garden scheme,[2] leftover, as it was, from medieval times.[3]

The Elizabethan gardens of the wealthy involved acres of land with numerous planted beds, as well as many other elements. Some of these were benches, fountains, architectural elements such as columns, heraldic elements, topiary and clipped shrubs, potted plants of various kinds, statuary, sundials, pathways, cisterns, reflecting pools, and arbors.[4] Toward the end of the period you see these in fantastic array, as well as large elements such as terracing, bowling greens, grottos, large gazebos and pergolas, banquet halls where dining might take place, small temples, labyrinths, mounts, and groves of trees.[5]

The Elizabethan gardens had a wide variety of plants. They included both native English plants and exotic, or “outlandish,” plants from all over the world. There was also a great deal of experimentation with plants, creating hybrids in many varieties. Both useful plants, and those grown purely for the pleasure of their beauty or scent were used. Plants might be left in their natural state, or shaped, as the hedges and topiary, or espalier trees.

Garden Design

Like many trends in the Renaissance, garden designs of this period began in Italy in the 15th century. We know a great deal about these gardens from agricultural treatises, literary sources, travel journals, paintings, and architects drawings. Most of the elements found in Elizabethan gardens began in Italy and traveled to England by way of France and the Low Countries.[6] The design of these gardens was architectural in nature, and the Italian Renaissance garden ushered in the concept of landscape architecture. The main concepts involved in the design of the gardens were classical formalism, linear perspective, and geometry.[7] The recreation of the “villa” ideal of Pliny the Elder was a potent influence on the reshaping of the garden in Italy.[8] But it is also clear from the literature that creating a beautiful garden was also seen as an attempt to recreate Eden—the perfect garden of the Bible. And perfection required control over the chaos of the natural world, which explains the obsession with geometry in garden design.[9] The garden became a meeting point for science and art as people tried to create a place where they could live in harmony with themselves and nature—an earthly paradise recovered.[10]

In England in the 16th century, there was a great desire by the nobles and wealthy to acquire manor house estates in the countryside. Because these homes did not need to be defensible, as they often did in the middle ages, they could have expansive gardens. As a result, the country house became a common element of the English landscape.[11] This manor house system persisted in England for generations longer than elsewhere in Europe; well out of our period and into the Victorian. [12]

There were some design elements that were particular to the English Renaissance garden that deserve special note. The most important of these is the use of the “knot” or beds to make up the garden, whether it was a functional kitchen garden or a pleasure garden. Other elements of importance are: rectangular, cross axis gardens at the sides of the house, a large straight path near the house called a “forthright,” a “mount” or small hill from which the garden can be viewed, a bowling green, covered walkways, mazes, topiary, and architectural elements.[13] Another important feature that is distinctly English is the incorporation of the kitchen garden into the formal garden.[14] Although architectural elements were important in the English Renaissance garden, architecture itself as a design element was not introduced until out of our period, about 1620.[15]

It should also be noted that many of the grand gardens were designed with Queen Elizabeth in mind. She often made progresses throughout the country, staying with her various nobles at their estates. Because of this, her particular symbols were often incorporated into the gardens. The Tudor rose was used heraldically, and the English wild rose, or eglantine, was planted in the gardens to honor her.[16]

Some of the designers of gardens are still known. John Thorpe was an architect who planned a number of gardens.[17] The only known designer of the intricate knot shaped gardens was Thomas Trevelyon, who also designed embroidery.[18]

Garden Uses

As noted previously, kitchen gardens were often incorporated into a formal setting, though they could be separate as well. Obviously, the kitchen garden was used to provide vegetables and herbs. But even the formal gardens had plants that were used for distilling perfumes and liquors, medicines, nosegays, strewing, or making “sweet bags” and other scented items.[19] Beyond the uses of the plants were the uses of the gardens as a whole for entertaining, meditating, and as a symbol of wealth.

Al fresco dining under tents or large gazebos, as well as masques and dances were often held in the garden in summer.[20] Often the gazebos were built on the top of the mount, so that diners could enjoy the view of the garden while eating. Masques and dances could be held on the large bowling greens. Of course, the bowling greens were also used for sport. Bowling, or “bowles,” as it was known then, was very popular in 16th century England. Another fashionable sport was tennis, and bowling greens could be converted to tennis courts, or there could be separate grass courts in the garden.[21]

The pleasure gardens of England were designed to appeal to all the senses, and the benches, viewing areas, and covered walkways were set up to create an atmosphere that was relaxing and meditative.[22] Splashing water features and birds appealed to hearing, the odor of the herbs and fragrant flowers to smell, the changes from shade to sun, pleasant breezes, and cool waters appealed to feel, the taste of the fruit from the trees to taste, and of course, the beauty of the whole garden to sight.[23]

The importance of the garden as a symbol of aristocratic magnificence should not be underestimated. Elaborate gardens were a form of important conspicuous consumption. Often the arms of the owner’s ancestors up to the present were prominently displayed, showing the noble heritage. There was a great deal of competition to get and keep the best gardeners and garden designers. The first elaborate gardens in England, built by Henry VIII, were a symbol of that monarch’s power.[24]

Garden Beds

The most important element of any of these gardens was the beds themselves. The beds of this period were always raised beds. This facilitates drainage, helps separate the plants from the surrounding area, and makes the beds somewhat easier to weed and water. Often a large bed would be divided into several smaller beds, which would be separated by walkways or paths.[25] It is only the actual planted area that was raised.

The materials used to raise the beds were quite varied. They used timbers, bricks, tiles, and quarried rock.[26] The beds were usually raised only a few inches. If a plant was wanted higher than that, pots were employed. Likewise, a variety of materials were used in the beds around the plantings. Although the most common was simply black soil, red brick dust, white sand, and pebbles of a variety of colors could be used to outline or fill in the areas of knot work designs not filled by plants.[27] Some beds were planted with, or surrounded by hedge plants. Tight hedges can be shaped easily, and hedge plants often make good topiary, which was very popular in the gardens.

The division of large beds into four sections, separated by a cross shaped pathway was typical of English gardens of this period. The smaller beds might then be subdivided or not, depending on size, but the four quadrant plan was by far the most common in England, and was a holdover from medieval times. Where circular beds were employed, a large tree was usually planted in the center. In rectangular or square beds, some other type of element was usually found where the paths came together in the center.[28] Fountains were popular for large beds, topiary, sculpture, or architectural elements for smaller ones.

The pathways could be grass, rock, sand, stone, or brick. They might be covered, or be open to the sky. Arbors were used extensively, usually intermittently, but occasionally in a continuous manner. A continuous arbor was called a “pleached alley.” [29]Often benches were placed in strategic locations so that those enjoying the garden might sit and enjoy a particularly nice view. There were often borders around the beds as well. These might be plants or other materials such as lead, timbers, tiles, or even bone.

Paintings of the period often show many different kinds of flowers in a single bed, planted often in clumps with large amounts of soil showing.[30] How plants were grouped in beds would have been decided by aesthetics, the growing conditions needed, and also by astrology and alchemy as well. Kitchen gardens or herbal gardens, on the other hand, would have separated plants by type.

Garden Plants

The plants in the Elizabethan garden varied from practical to whimsical, and native to “outlandish.” Traditional plants continued to be very popular. Among these were violets, cowslips, primroses, lilies, gillyflowers, periwinkle, and all varieties of roses. Arbors could be covered with ivies or other climbing plants. Hedges were made of hawthorn, juniper, holly, elm, ilex, and box, as well as other shrubs. Thrift, germander, box, marjoram, savoury, and thyme were popular border plants.[31]

Practical plants like comfrey, rosemary, parsley, sage, and mint were also grown. Not only did these plants have use, they also provided pleasant aromas to the garden. The 16th century was the heyday of the cult of herbs, and they were cultivated for medicine, cooking, alchemy, and garden ornament.[32] Herbal medicines were prized, and most manor houses had a “stilling house” for the manufacture of them, as well as perfumes and potables.

Plants from all over the world were imported for use in English gardens as well. Some of the most popular were daffodils, hyacinths, crocus, tulips, anemones, cyclamen and many of the hellebores, particularly the “Christmas Rose.”[33] The study of botany was just coming into its own in England, and the study of botanical specimens was a popular hobby. Gerard, of herbal fame, employed William Marshall as a collector to find exotic plants from all over the world.[34] Nicholas Leate, a London merchant, traded in plants from Turkey, and also hired collectors to find new plants for him. He was also an experimenter in hybrids and grafting techniques.[35]

Plants that could not survive the winter were often grown in pots, and placed strategically throughout the garden. Citrus trees were quite often done this way, although hardy topiaries were also often grown in pots so they could be moved around as desired.

Large trees were found in groves and grottos. Pines, cypresses, laurels, elms, maples, ashes, oaks, aspens, yews, and poplars were all found in gardens. Groves of myrtle are also described in the literature.

Gardens of the Period

Many gardens that existed in this period are known, though none still exists in its original form. Because many of them were described in letters, we do have an idea of what some of them looked like.

Theobalds was modeled on and Italian plan, and it was the most Italian garden in England. It was the country garden of William Cecil. It had a moat or canal that surrounded it and a grotto. The whole garden was about seven acres in size. The “privy garden” part of it was enclosed by a wall, in the medieval style, and also had gravel walks, cherry trees, and hedges cut into various shapes. In the “great garden” there were knots gardens of various types and a large marble fountain. The surrounding canal was large enough for boating.[36]

Nonsuch, started by Henry VIII in 1538,[37] was redesigned and completed by Lord Lumley in the 1580s. He had been to Italy to view the gardens there, and he incorporated many of those elements into the garden. He planted many small groves or clumps of trees and shrubs, but the garden was still laid out in knots. He had his heraldry prominently displayed, topiary animals, marble columns and pyramids, fountains, and sculpture. But he also included less formal elements such as the “grove of Diana” that contained a grotto.[38]

Kenilworth Castle had bowers, arbors, and walkways with seats. It also boasted an aviary. The large square garden was divided into quarters with a fountain where the grass walks edged in sand intersected. There was an obelisk on each of the quarters surrounded by fragrant plants and herbs and fruit trees. There was also heraldry used as a decorative element. This was the first example in England of terracing used for viewing the gardens.[39]

Cobham Hall was finished in 1586. It was known for having for varieties of rare plants and flowers than any other garden of its time. It also had an arbor made of a living lime tree, one of the more intricate examples of espalier.[40]

Garden Manuals and Herbals

The first description of an English garden may have been in the 13th century when John de Garlande published Dictionarus.[41] The love affair with gardens in England continued, and many manuals, herbals, and other gardening books were published. In the 16th century, practical gardening manuals tended to be written for the middle class, and herbals for the aristocracy.[42] This was due to the fact that many of the authors of the herbals had aristocratic patrons. William Cecil, who owned Theobalds, was the patron of John Gerard of herbal fame, William Turner, “the father of English botany,” and Matthias de l’Obel, for whom the flower lobelia is named.[43]

John Parkinson (1567-1650) published two botanical books. Although both were published out of period, much of the material was from the 16th century. His books are Paradisi in Sole, published in 1629, and Theatrum Botanicum, published in 1640. In his books he describes many of the plants and flowers typical in Elizabethan gardens. He is credited with the creation of the flower garden as an independent type of garden.[44]

The Gardener’s Labyrinth, published in 1571 by Thomas Hill shows rectangular, square, and circular raised beds used in a garden that had a dual purpose, including both useful and purely pleasure plants. As the name suggests, maze beds were also illustrated.[45]

Francis Bacon’s essay Of Gardens, published in 1625 (but based on his earlier 1597 works) details his ideal of what an Elizabethan garden should be. Although he is not very knowledgeable about plants or gardens, he has detailed descriptions of the types of things found in them.[46]

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Published in 1499 by Francesco Colonna describes all the elements of the Italian Renaissance garden.[47]

Piero de’Crescenzi wrote Liber Ruralium Commodorum between 1304 and 1309. It is a “how to” type book, that was extremely popular, and was republished in many languages throughout our period of discussion. A 16th century edition in the British Library included miniatures depicting the various activities described in the book. This was one of the most popular manuals of the period.[48]

Another manual was The Feate of Gardening by Mayster Ion Gardener, first published in 1400 as a five-page poem. It was later transcribed into a book of miscellanies around 1440.[49]

Thomas Tusser (1515-1580) wrote a manual for the yeoman gardener that was published in 1573 called Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry. It was written in rhymed couplets.[50]

Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim (1493-1541) was a physician who wrote extensively about plants. He wrote under the name “Paracelsus” and is best know for a treatise based on the “Doctrine of Signatures,” a popular, if incorrect, theory of plants.[51]

William Turner published his first herbal in 1538, another in 1548, and his third in 1568. This latter was the first herbal to contain New World plants.[52] Turner was called the “father of English botany,”[53] and he collected dried specimens of the plants he wrote about.

The best-known herbals of the period were written by John Gerard. His Herball or Generall Histories of Plantes was published in 1597.[54]

[1] Gorer, 12

[2] Strong, 46

[3] Pregill, 232

[4] Llewellyn, 74-97

[5] Singleton, 15-16

[6] Strong, 13

[7] Pregill, 207

[8] Strong, 13

[9] Comito, 14

[10] Beretta, 38

[11] Pregill, 231

[12] Tobey, 120

[13] Tobey, 122-124

[14] Tobey, 124

[15] Strong, 15

[16] Strong, 46-47

[17] Singleton, 23

[18] Strong, 70

[19] Singleton, 4 and 54-55

[20] Strong, 11

[21] Hyams, 144

[22] Beretta, 163

[23] Beretta, 68

[24] Strong, 10

[25] Singleton, 40

[26] Gorer, 7

[27] Strong, 33

[28] Singleton, 42

[29] Singleton, 50

[30] Singleton, 42

[31] Gorer, 6

[32] Cooper, 23

[33] Singleton, 78-81; A. Coats, 112-113

[34] Singleton, 34

[35] Singleton, 36

[36] Strong, 52-53

[37] Strong, 38

[38] Strong, 63-66

[39] Strong, 50-51

[40] Strong, 69

[41] Singleton, 8

[42] Comito, 20-22

[43] Comito, 19

[44] Singleton, 31

[45] Cooper, 28

[46] Gorer, 9-10

[47] Singleton 15; Lazzoro, 21

[48] Calkins, 157-163; Hyams, 92

[49] Hyams, 95

[50] Fisher, 56-57

[51] Fisher, 40

[52] Fisher, 53-54

[53] Hyams, 144

[54] Fisher, 57-58

Sources

The Renaissance Garden in England, Roy Strong, 1979

The Flower Garden in England, Richard Gorer, 1975

The Idea of the Garden in the Renaissance, Terry Comito, 1935

The World’s a Garden; Garden Poetry of the English Renaissance, Ilva Beretta, 1993

The Origins of Garden Plants, John Fisher, 1982

Flowers in History, Peter Coats, 1970

Flowers and Their Histories, Alice W. Coats, 1956

The Architecture of the Renaissance in France, vol. I (1495-1640), W.H. Ward, 1926

Formal Gardens in England and Scotland, H. Inigo Triggs, 1988

Ornamental English Gardens, Roddy Llewellyn, 1990

The Italian Renaissance Garden, Claudia Lazzoro, 1990

Medieval Gardens, Elisabeth B. MacDougall, ed., 1986

Landscapes in History, Philip Pregill & Nancy Volkman, 1993

A History of Landscape Architecture, G.B. Tobey, 1973

Flowers Through the Ages, Gabriele Terget, 1962

A History of Gardens and Gardening, Edward Hyams, 1971

Oxford English Dictionary On-line

The Early English Kitchen Garden, Mary Palmer Cooper; a thesis submitted at Louisiana State University for a Master of Landscape Architecture, 1977

The Shakespeare Garden, Esther Singleton, 1931

The Medieval Garden, Sylvia Landsberg, no date listed, ISBN 0-500-01691-7

The Renaissance Garden in England, Roy Strong, 1979

The Flower Garden in England, Richard Gorer, 1975

The Idea of the Garden in the Renaissance, Terry Comito, 1935

The World’s a Garden; Garden Poetry of the English Renaissance, Ilva Beretta, 1993

The Origins of Garden Plants, John Fisher, 1982

Flowers in History, Peter Coats, 1970

Flowers and Their Histories, Alice W. Coats, 1956

The Architecture of the Renaissance in France, vol. I (1495-1640), W.H. Ward, 1926

Formal Gardens in England and Scotland, H. Inigo Triggs, 1988

Ornamental English Gardens, Roddy Llewellyn, 1990

The Italian Renaissance Garden, Claudia Lazzoro, 1990

Medieval Gardens, Elisabeth B. MacDougall, ed., 1986

Landscapes in History, Philip Pregill & Nancy Volkman, 1993

A History of Landscape Architecture, G.B. Tobey, 1973

Flowers Through the Ages, Gabriele Terget, 1962

A History of Gardens and Gardening, Edward Hyams, 1971

Oxford English Dictionary On-line

The Early English Kitchen Garden, Mary Palmer Cooper; a thesis submitted at Louisiana State University for a Master of Landscape Architecture, 1977

The Shakespeare Garden, Esther Singleton, 1931

The Medieval Garden, Sylvia Landsberg, no date listed, ISBN 0-500-01691-7

The knot garden I made at a former residence.