Period Sausage

Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 2013)

According to most dictionaries, sausage is minced meat, usually stuffed in casings. It comes from the Latin salicia; seasoned with salt, through the Old French word sausiche, and into the Middle English word sausige. Sausage is mentioned numerous times in the cooking manuscripts that we have available to us. Medieval manuscripts tend to call it sausage only when it is stuffed into animal intestine casings or sometimes caul, which is the membrane that surrounds the intestines. When it is stuffed in a stomach or womb, it is usually called haggis, and when it has no casing, it is called “forcemeat.” Sausage has a reputation for being made from the scraps and off-cuts of animals that might otherwise be unusable. Although this is not always true, it certainly could be, both then and now. However, what we now call off-cuts, were sometimes popular meat cuts in period. Tripe (stomach), trotters (pigs’ feet), liver, sweetbreads (thymus gland), testicles, and hearts were all popular dishes for the wealthy in various periods. In fact, many of these are undergoing a comeback in haute cuisine today. Blood sausages, or black pudding in England, and bludwurst in Germany, are popular sausages to this day. Liver sausage also continues in popularity.

In researching sausages from various SCA period cultures, it is clear that the wealthy, for whom period cookbooks catered, got very good cuts of meat in their sausage. Most sausage recipes from period called for pork leg, pork shoulder (butt), back bacon, and pork belly as ingredients. Sausage has a high fat content, and the fats used were likewise the best. Rendered fats, like lard were not much used. It was the hard clean fats from the back and belly that are most often called for. Likewise, the rich wanted their sausage heavily seasoned with the expensive spices and herbs used in other dishes. Cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, saffron, pepper, grains of paradise, long pepper, ginger, mustard and herbs such as marjoram, parsley, dill, fennel seed were common ingredients. You might also see nuts, fruits, grains, and cheeses included. Where modern sausage tends to have a few strong spices like mustard powder, garlic, and hot peppers, period sausages had more subtle complex flavors. Texture is one of the most important elements of good sausage. We use grinder today. In period, the meats and fat were either chopped very fine with knives, or pulverized in a mortar. Once packed into the casings and cooked, you get a “snap” when you pierce the casing and a compact meat product within that is free from chunks or lumps.

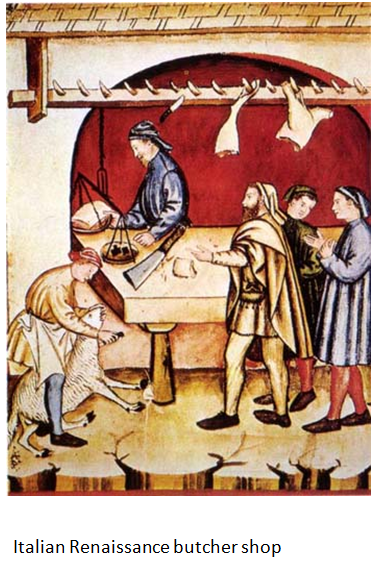

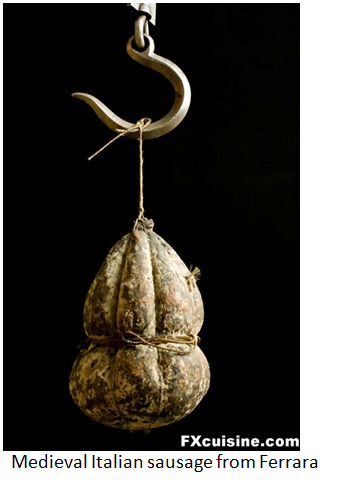

Sausage making undoubtedly started in the home, but throughout SCA periods there were also professional butchers and sausage makers. The very wealthy had professional cooks that might make sausages for them, but sausage, like cheeses, often came from professionals. It is also likely that lesser quality sausages figured prominently in the food stalls that provided the majority of food for the inner-city poor in the large medieval cities, like London and Paris. Often the tenements of the poor had no access to cooking facilities, requiring them to get their meals from an employer or from “fast food” stalls. Because sausages are portable, protected from the elements by their casings, and can be cooked over a small fire quickly, they make an excellent fare for a food stall. There are also methods for prolonging the shelf life of sausages. Both smoking and curing were known in SCA periods. Smoking usually consisted of hanging the sausages well above a smoky fire and letting them smoke slowly. Curing was done most often with salt and spices, then ageing, but curing with sodium nitrate, saltpeter, was also known.

Why sausage? After some friends of mine and I got together to make modern sausages, and discovered that our own were highly superior to anything in a store, we became interested in period sausages as well. This led to a yearlong arts and sciences quest which became The Sausage Project. Over the year we made five very different types of sausages from five different cultures, each with an appropriate accompanying sauce. I have listed the web page for the documentation and photos in the bibliography section of the hand-out. We entered this in our Kingdom Arts and Sciences Faire in May of 2013. We scored 19.5 out of 20.

The Sausage Project:

Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 2013)

According to most dictionaries, sausage is minced meat, usually stuffed in casings. It comes from the Latin salicia; seasoned with salt, through the Old French word sausiche, and into the Middle English word sausige. Sausage is mentioned numerous times in the cooking manuscripts that we have available to us. Medieval manuscripts tend to call it sausage only when it is stuffed into animal intestine casings or sometimes caul, which is the membrane that surrounds the intestines. When it is stuffed in a stomach or womb, it is usually called haggis, and when it has no casing, it is called “forcemeat.” Sausage has a reputation for being made from the scraps and off-cuts of animals that might otherwise be unusable. Although this is not always true, it certainly could be, both then and now. However, what we now call off-cuts, were sometimes popular meat cuts in period. Tripe (stomach), trotters (pigs’ feet), liver, sweetbreads (thymus gland), testicles, and hearts were all popular dishes for the wealthy in various periods. In fact, many of these are undergoing a comeback in haute cuisine today. Blood sausages, or black pudding in England, and bludwurst in Germany, are popular sausages to this day. Liver sausage also continues in popularity.

In researching sausages from various SCA period cultures, it is clear that the wealthy, for whom period cookbooks catered, got very good cuts of meat in their sausage. Most sausage recipes from period called for pork leg, pork shoulder (butt), back bacon, and pork belly as ingredients. Sausage has a high fat content, and the fats used were likewise the best. Rendered fats, like lard were not much used. It was the hard clean fats from the back and belly that are most often called for. Likewise, the rich wanted their sausage heavily seasoned with the expensive spices and herbs used in other dishes. Cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, saffron, pepper, grains of paradise, long pepper, ginger, mustard and herbs such as marjoram, parsley, dill, fennel seed were common ingredients. You might also see nuts, fruits, grains, and cheeses included. Where modern sausage tends to have a few strong spices like mustard powder, garlic, and hot peppers, period sausages had more subtle complex flavors. Texture is one of the most important elements of good sausage. We use grinder today. In period, the meats and fat were either chopped very fine with knives, or pulverized in a mortar. Once packed into the casings and cooked, you get a “snap” when you pierce the casing and a compact meat product within that is free from chunks or lumps.

Sausage making undoubtedly started in the home, but throughout SCA periods there were also professional butchers and sausage makers. The very wealthy had professional cooks that might make sausages for them, but sausage, like cheeses, often came from professionals. It is also likely that lesser quality sausages figured prominently in the food stalls that provided the majority of food for the inner-city poor in the large medieval cities, like London and Paris. Often the tenements of the poor had no access to cooking facilities, requiring them to get their meals from an employer or from “fast food” stalls. Because sausages are portable, protected from the elements by their casings, and can be cooked over a small fire quickly, they make an excellent fare for a food stall. There are also methods for prolonging the shelf life of sausages. Both smoking and curing were known in SCA periods. Smoking usually consisted of hanging the sausages well above a smoky fire and letting them smoke slowly. Curing was done most often with salt and spices, then ageing, but curing with sodium nitrate, saltpeter, was also known.

Why sausage? After some friends of mine and I got together to make modern sausages, and discovered that our own were highly superior to anything in a store, we became interested in period sausages as well. This led to a yearlong arts and sciences quest which became The Sausage Project. Over the year we made five very different types of sausages from five different cultures, each with an appropriate accompanying sauce. I have listed the web page for the documentation and photos in the bibliography section of the hand-out. We entered this in our Kingdom Arts and Sciences Faire in May of 2013. We scored 19.5 out of 20.

The Sausage Project:

- Lucanian Sausage—The original recipe appears in Appicius and dates to the 5th century C.E. These sausages were probably indroduced to Rome from Greece in the 2nd century B.C.E. Although Platina referred to Lucanian sausage by name in his 15th century cookbook, it was a very different product by that time. Roman Lucanicae are very thin pork sausages stuffed in sheep casings and lightly smoked. Their characteristic flavors come from the smoke, pine nuts, bay berries, a large variety of herbs, and, of course, fish sauce, or liquamen. Do not be afraid of fish sauce. It is making a comeback in modern haute cuisine for a reason. Fish sauces, when used with a light hand, are flavor enhancers that bring out the other flavors of the food they are in. If you like Worcestershire Sauce, which contains anchovy, you will probably like the other fish sauces as well. We paired this sausage with a oenogarum, or wine-garum sauce. Yep, more fish sauce, mixed with Italian white wine, reduced white wine, and a large number of herbs that were commonly used in sauces. This sauce was not particularly fishy—we used a very high quality anchovy extract from Italy. The sauce had both fatty and acidic notes and the fresh green flavor of the herbs. It paired very well with the sausages. We grilled these sausages right before serving.

- Herrisons—These are tiny French sausages that date from the 14th century from The Viander of Taillevant. Herrisons means ” hedgehogs,” so named because of their small round shape. These are also stuffed into lamb casings and tied off quickly to form almost a string of sausage “beads.” These contain pork, cheese (we used Brie), fresh grapes, and poudre fine, a mixture of spices and sugar. We paired these with a cameline sauce; a red wine based sauce with many of the same spices as the sausage. These sausages are so moist from the grapes that the juice squirts in your mouth when you bite down on them. We boiled these very quickly (about 5 minutes) just before serving.

- White Pudding—This is a pork liver sausage stuffed in pork casings from Elizabethan England. Even people who swore they did not like liver, liked this sausage. The liver flavor was somewhat mellowed by the significant amount of heavy cream and eggs, dried fruits and spices. We also used a very high quality liver, grown organically on a local farm, free of all membrane. This sausage was cooked in advance, as sausages from organ meats are inclined to spoil quickly. We froze it for storage, then thawed it and served it at room temperature. The texture did become a bit grainy from freezing, but the flavor was not affected. We paired this with a near scalding mustard containing yellow mustard, onion, horseradish, white pepper, and ginger—five different kinds of heat. Although hot, this complex flavor profile was quite good. The provenance of this recipe is suspect, but I have found very similar mustards in Elizabethan sources.

- Mortadella—This classic Italian sausage is still made today, though the ingredients and flavor profile have changed. This is a home-cured sausage, which sits or hangs for a period of time before eating. Our version came from the Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570). This was a challenging sausage to make, not only because it cures, but because it is a large sausage that is wrapped in pig caul rather than packing it into casings. The flavors of ours included a number of fresh herbs; dill, marjoram, spearmint, and thyme, as well as pepper, cinnamon, and clove. We chose to add a small amount of modern curing mixture, just to be safe. After being wrapped tightly in the caul, it is wrapped again in cheesecloth soaked in melted lard. Then the ends are twisted in opposite directions to compact the meat mixture. We wrapped it in heavy twine and hung it in my garage for three days with a fan blowing on it. After three days I wrapped in plastic wrap, then foil, and froze it. We did not know if the texture was right until we cut into it right before cooking and serving. Luck was with us—it was perfect. We cut it in 1 inch slices then into lardoons and fried these in bacon fat. We drained them on paper towels then placed them in a bowl and immediately squeezed a fresh Valencia orange over it for a sauce. This was my favorite of our sausages.

- Bratwurst—This classic German sausage dates back at least to the 16th century. Our recipe came from the Sabina Welserin Cookbook available on-line. Unlike the modern sausage with its strong pepper and mustard flavors, our version was more delicate with floral notes from the fresh herbs. It contains both beef and pork, stuffed into pork casings. We paired this with a honey-mustard, recipe from An Early Northern Cookery Book, which also contained anise and cinnamon. The mustard is good enough to spread on bread and eat by itself. We grilled these sausages right before serving.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Roman

Apicius, Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger, trans., 2006, ISBN 1-903018-13-7

Around the Roman Table, Patrick Faas, 1994, ISBN 0-312-23958-0

The Classical Cookbook, Andrew Dalby and Sally Grainger, 1996, ISBN 0-89236-394-0

Italian

The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570), Terrance Scully, trans., 2008, ISBN 978-0-8020-9624-1

Platina: On Right Pleasure and Good Health (De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine), Mary Ella Milham, trans., 1998, ISBN 0-86698-208-6 (15th cent.)

“Lost in Translation—Problems with the Scully translation of Scappi,” a class taught by Helewyse de Birestad, OL at Pennsic War 2009.

French

The Vivendier, Terrence Scully, trans., 1997, ISBN 0907325815

Fêtes Gourmands, Jean-Louis Flandrin and Carole Lambert, 1998, ISBN 2-7433-0268-2 (translated by Micaela Burnham into English)

The Viander of Taillevent: an Edition of all Extant Manuscripts, Terence Scully, ed., 1988, ISBN 0-7766-0174-1

Cheese and Culture, Paul S. Kindstadt, 2012, ISBN 978-1-60358-411-1

The Original Mediterranean Cookbook, Barbara Santich, 1995, ISBN 0907-325-59-9

The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy, Odile Redun, François Sabban, and Silvano Serventi, 1991, ISBN 0-226-70684-2

English

Cocatrice and Lampray Hay, Constance. B. Hieatt, trans., 2012, ISBN 978-1-903018-84-2

Dining with William Shakespeare, Madge Lorwin, 1976, ISBN 0-689-10731-5

All the King’s Cooks, Peter Brears, 1999, ISBN 0-285-63533-6

The Good Housewife’s Jewel (1596-1597), Thomas Dawson, 1996, ISBN 1-870962-12-5

Take a Thousand Eggs or More, Vol. 2, Cindy Renfrow, 1991, self-published originally, it now has been published by Royal Fireworks Press.

German

Daz bůch von gůter spice (The Book of Good Food), Melitta Weiss Adamson, 2000, ISBN 3-90-1094-12-1

Libellus de arte coquinaria : An Early Northern Cookery Book, Rudolf Grewe and Constance B. Hieatt, eds. and trans., 2001, ISBN0-86698-264-7

The Sabina Welserin Cookbook, 1553, Valoise Armstrong, trans., 1998

http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Medieval/Cookbooks/Sabrina_Welserin.html

General

The Book of Sent Sovi, Joan Satanach, ed., Robin M. Vogelzang, trans., 2008, ISBN 978-1-85566-164-6

The Domostroi, Carolyn Johnston Pouncy, trans., 1994, ISBN 0-8014-2410-0

From Julia Child’s Kitchen, Julia Child, 1975, ISBN 0-394-48071-6

Food and Feast in Medieval England, P.W. Hammond, 1993, ISBN 0-7509-0992-7

The English Hus-wife, Gervase Markham, 1615

Roman

Apicius, Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger, trans., 2006, ISBN 1-903018-13-7

Around the Roman Table, Patrick Faas, 1994, ISBN 0-312-23958-0

The Classical Cookbook, Andrew Dalby and Sally Grainger, 1996, ISBN 0-89236-394-0

Italian

The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570), Terrance Scully, trans., 2008, ISBN 978-0-8020-9624-1

Platina: On Right Pleasure and Good Health (De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine), Mary Ella Milham, trans., 1998, ISBN 0-86698-208-6 (15th cent.)

“Lost in Translation—Problems with the Scully translation of Scappi,” a class taught by Helewyse de Birestad, OL at Pennsic War 2009.

French

The Vivendier, Terrence Scully, trans., 1997, ISBN 0907325815

Fêtes Gourmands, Jean-Louis Flandrin and Carole Lambert, 1998, ISBN 2-7433-0268-2 (translated by Micaela Burnham into English)

The Viander of Taillevent: an Edition of all Extant Manuscripts, Terence Scully, ed., 1988, ISBN 0-7766-0174-1

Cheese and Culture, Paul S. Kindstadt, 2012, ISBN 978-1-60358-411-1

The Original Mediterranean Cookbook, Barbara Santich, 1995, ISBN 0907-325-59-9

The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy, Odile Redun, François Sabban, and Silvano Serventi, 1991, ISBN 0-226-70684-2

English

Cocatrice and Lampray Hay, Constance. B. Hieatt, trans., 2012, ISBN 978-1-903018-84-2

Dining with William Shakespeare, Madge Lorwin, 1976, ISBN 0-689-10731-5

All the King’s Cooks, Peter Brears, 1999, ISBN 0-285-63533-6

The Good Housewife’s Jewel (1596-1597), Thomas Dawson, 1996, ISBN 1-870962-12-5

Take a Thousand Eggs or More, Vol. 2, Cindy Renfrow, 1991, self-published originally, it now has been published by Royal Fireworks Press.

German

Daz bůch von gůter spice (The Book of Good Food), Melitta Weiss Adamson, 2000, ISBN 3-90-1094-12-1

Libellus de arte coquinaria : An Early Northern Cookery Book, Rudolf Grewe and Constance B. Hieatt, eds. and trans., 2001, ISBN0-86698-264-7

The Sabina Welserin Cookbook, 1553, Valoise Armstrong, trans., 1998

http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Medieval/Cookbooks/Sabrina_Welserin.html

General

The Book of Sent Sovi, Joan Satanach, ed., Robin M. Vogelzang, trans., 2008, ISBN 978-1-85566-164-6

The Domostroi, Carolyn Johnston Pouncy, trans., 1994, ISBN 0-8014-2410-0

From Julia Child’s Kitchen, Julia Child, 1975, ISBN 0-394-48071-6

Food and Feast in Medieval England, P.W. Hammond, 1993, ISBN 0-7509-0992-7

The English Hus-wife, Gervase Markham, 1615