The Bedouin Costume Project

Bedouin Woman’s Special Occasion Garment c. 1450

Researched and constructed by: Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia, Master Ronayne Blackwell, Lady Francesca d’Angelo, Mistress Maysun & Lady Marina MacChruiter (Micaela Burnham, author; copyright all 2000)

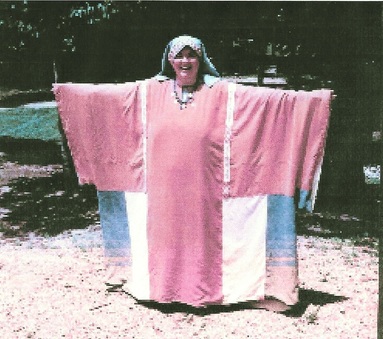

This garment attempts to replicate what a Bedouin woman might have worn on a special occasion, such as a wedding, ceremonial occasion, or important religious rite. The time period is mid-15th century. The garments consist of pants, under robe, over garment, veil, and shoes with attached knitted cuffs.

The over garment, a large thobe, is constructed of heavy silk, which has been dyed with indigo, saffron, cochineal, and madder. The seams are felled and finished by hand. The tiraz bands are typical of special occasion garments for both sexes in this period on the Arabian Peninsula. They are tablet woven in silk thread (purchased) that has been hand dyed, and they are decorated with Arabic script phrases. The undergarments and veil are constructed of a linen and cotton blend, well known in this period, and dyed with indigo. They are embroidered at the cuffs of the arms and legs and the headband with period style designs in hand spun silk thread that is dyed with saffron and cochineal. The seam allowances are turned back and finished by hand. Construction techniques, patterns, fabrics, dyes, threads, and embroidery designs and stitches can be documented to the medieval Middle East, but not always to this specific area or time. Because few extant garments exist, and no Bedouin garments have been found, we have drawn on sources from surrounding areas and time periods to arrive at this final garment. Using costume evolution theory, and the available resources, we believe that we have made a good estimate of what might have been worn.

Lady Francesca did the spinning and dyeing. Master Ronayne wove the tiraz bands. Mistress Maysun made the leather shoes, and Lady Marina knitted the cuffs. Magistra Rosemounde developed the patterns, constructed the garments, made the sprang drawstring, made the over garment button, and did all of the embroidery.

The Garments

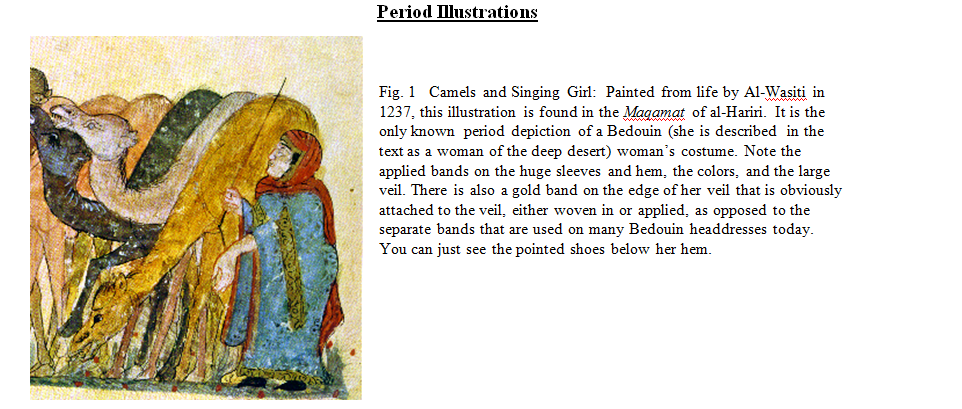

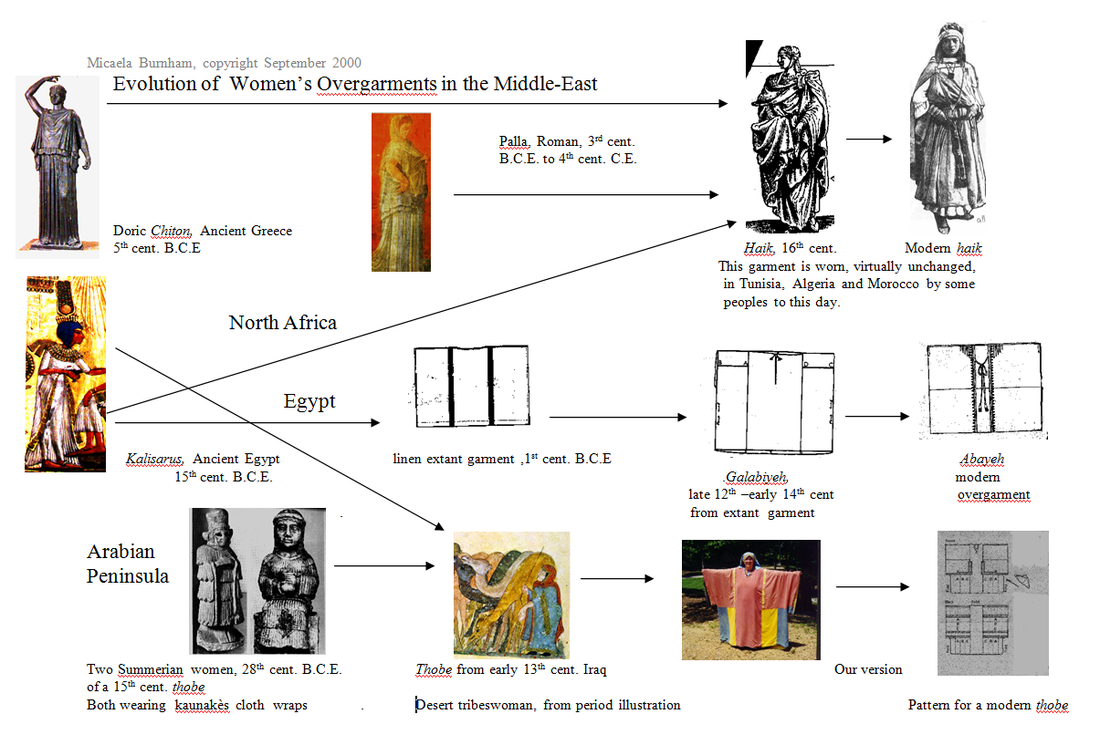

Some form of large woman’s over garment dates back to earlier garments found in ancient Persia, Sumerian, and Egypt. Often these garments were simply a very large rectangle of fabric that was folded or draped. The only visual depiction of this garment we have found in the medieval periods is dated 1237 C.E., and is identifiable as the traditional folk garment of Arabian Bedouins, now called the majestic thobe. It is also similar in many ways to the aba or abayeh, a garment also found both in period and today, as they both developed from the same ancient garments. There was a type of chemise (qamis) in the 14th century that was long and trailing with extremely wide sleeves, which is described as having sleeves like Bedouin garments. This type of garment may have influenced this style of chemise. The period depiction that we have of the thobe differs from the modern or folk garment in several ways, which enables us to follow its evolution to some extent. The period garment does not have a train, and the decorative bands appear in different areas of the garment. It also has smaller sleeves. It is impossible to tell if there are gussets, but as the garment is very full under the sleeve, this would be an affectation rather than a necessity.

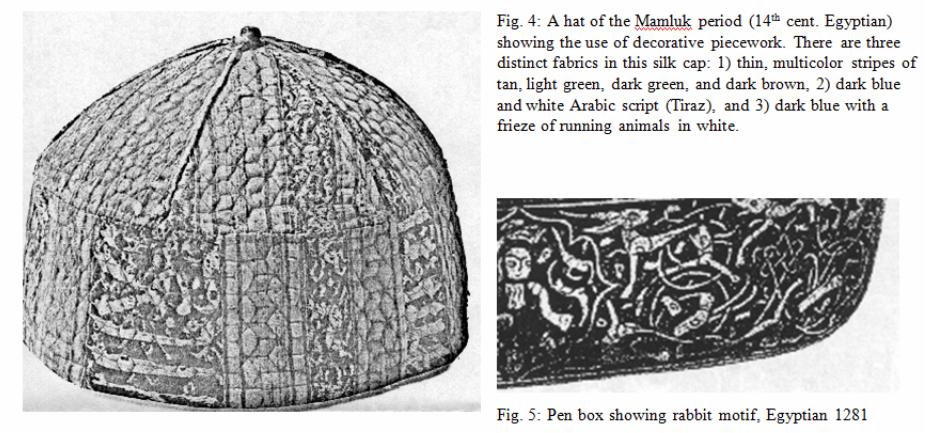

Because the only visual depiction of the garment is an every day garment (the woman is tending camels), it is difficult to know what differences we would have seen in a festive garment. Other garments of the period are made special in a variety of ways: application of embroidery, use of expensive and highly decorative fabrics, and the addition of decorative bands, especially tiraz. We used silk, an expensive fabric, and added tiraz bands. In addition we used decorative piecing to enhance the look of the garment. This technique is extremely common in the modern version of the garment, but is harder to place in period. The Persians loved to mix different fabrics in an outfit, but it is not until the 17th century that we have clear pictures of fabrics being pieced in a single garment there. In Arabia in this period, we do see the use of contrasting exterior facings of different fabrics, and there is an extant 15th century cap from Egypt where striped fabric has been pieced with fabric painted with tiraz. A 10th to 12th century garment from North Africa caleed a muraqqa’a, was a patchwork over dress, and examples of large patchwork were found on women’s robes in North Africa well into our period. There are also extant examples of piecework used in combination with embroidery, but on a smaller scale than this piece. In any case, an overgarment was typical of Arab women’s clothing for outdoor wear.

The thobe worn as the undergarment was typical of Arabian women’s clothing in this period. There are numerous depictions of Arabian women of the cities wearing a garment that is identical in look to the one we made. Extant garments with this same pattern exist from Egypt and Nubia, and it differs only slightly from Persian garments of the same period as well as those that came later. The pants pattern is also consistent with those found in the area. There are a number of extant garments and hundreds of visual depictions that bear this out. The veil, likewise, is common of the area and period and can be placed specifically as Arabian. The undergarments are made of a linen and cotton blend, which are documentable for garments of the time.

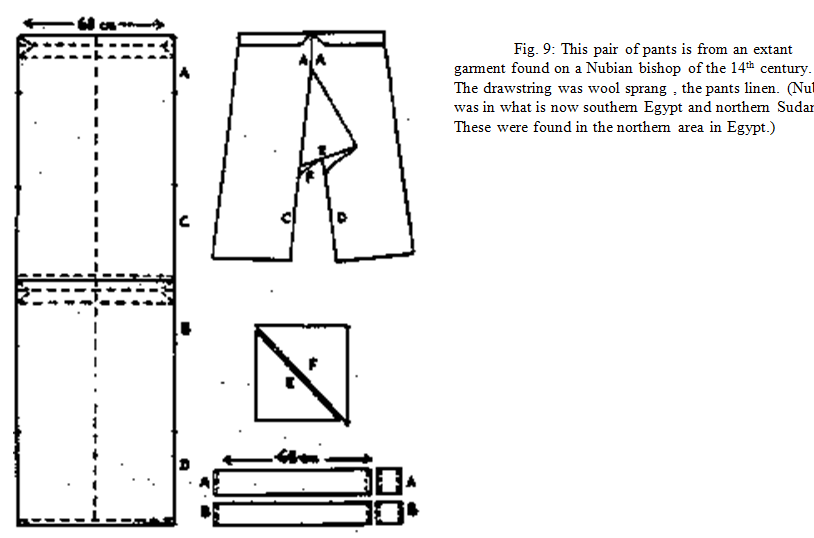

The drawstring in the pants is executed in sprang in a natural shade of dark brown wool. At least one drawstring of this type has been found in an extant garment of the period in Nubia. There are two buttons. The undergarment has a simple silver button worked from sheet silver. This was purchased and is similar to beads found in the area in period. The button on the over garment is a thread wrapped bead. This technique was widely used throughout Europe during the Renaissance and can be found on extant Turkish garments from the 16th century.

The Tiraz Bands

The word “tiraz” means “embroidered” in Persian, but many techniques were used for making these bands of trim. Also, the term has come to refer to trims that contain inscriptions in Arabic. Tiraz bands are found on both men’s and women’s garments from the 10th through the 16th centuries, although in the later periods they became more abstract. They were a common item in women’s trousseaux, and were most often worn on hems of garments, cloaks, sleeves, headbands, belts, drawstrings, and on scarves. Tiraz was found throughout the Middle East. These bands are silk, a common medium, and are hand dyed. They are gold and red; the most common colors used in tiraz. They are tablet woven. Although there are no extant examples of tablet woven tiraz in Arabia in this period, mid-15th century examples of tablet woven trims have been found in Egypt, some of which are the stylized form of tiraz. Tablet weaving was well known in the Arabian Peninsula as well, as it had been used there since ancient times. The pattern of these bands is original with some elements being based on period bands. The bands on this garment say, “The dreams of cats are all of mice” in Arabic. This is an Arabic proverb of unknown age, but believed to date back at least to this period.

The Embroidery

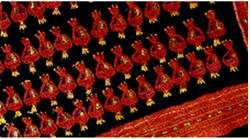

The embroidery on the undergarments and veil is done in hand spun silk thread that has been hand dyed. The designs are taken from period embroideries and fabric designs from the Arabian Peninsula. They are executed in chain stitch, outline stitch, satin stitch, and knotting, all of which were used in embroidery in the Middle East in this period. Extant examples can be found of all of these. The specific designs were chosen for a woman with no children. The rabbits, birds and pomegranates were all fertility symbols of the period. The hems of the over garment are finished with running stitches in contrasting colors. These are executed in purchased silk thread.

The Spinning and Dyeing

The hand spun silk and wool threads are Z spun and S plied, which appears to have been the standard in the Middle East during this period. The spinning was done on a drop spindle, the most common method of spinning in the region in period. Sprang, the treatment used for the drawstring, was found on an extant garment from the same period in a neighboring region. The dyes and mordants, likewise, can be documented to the Middle East in the mid 15th century. Indigo, saffron, cochineal (substituted for kermes, a chemically equivalent insect dye), and madder were all dyes used with frequency in the Middle East in this time period.

The over garment is 100% silk broadcloth. This fabric was initially a cream color. It was divided into 3 sections and one section was dyed with indigo, one in saffron, and one in madder and cochineal. Prior to dyeing and mordanting this fabric, it was washed in simmering water with detergent to remove any gum and chemicals from the processing of the fabric. The lining of the over garment is also silk, but of a lighter weight. It was also dyed with saffron.

The handspun silk embroidery thread was spun from silk bells, which resulted in a loose, fluffy yarn, which was able to readily accept the dye. The commercially spun silk cord was used to make the tiraz bands and was dyed in the same colors and the same methods as the handspun silk embroidery thread. The fabric for the undergarments is a cotton/linen blend fabric and was dyed with indigo.

SAFFRON: Both the yellow silk fabric and the yellow silk embroidery thread were dyed with saffron. Alum was the mordant used for the threads and the outer fabric. The saffron was first ground with a mortar and pestle. This method produced a brilliant yellow. The lining is a paler shade of gold, as an iron mordant was used with it to give it a more golden color.

MADDER/COCHINEAL: The red silk fabric was dyed with a base of madder and then over dyed with cochineal. The fuchsia silk embroidery thread was dyed with cochineal only. For both the red silk fabric and the silk embroidery thread the same alum mordant technique was used. However, the red silk fabric was mordanted twice because madder does not dye as effectively on silk fabric. The madder was broken up as small as possible and run through a grinder. We repeated the process to darken the color. In order to deepen the color further, we over dyed it in a solution of cochineal. The silk thread was dyed with cochineal only. The silk embroidery thread came out a rich fuchsia but the commercially spun yarn was not quite as rich as it was more tightly spun.

INDIGO: The process of indigo dyeing is chemically very different than the regular dyeing processes. We will assume that the readers have some knowledge of this. The linen/cotton fabric and the silk were both scoured prior to dyeing. Both the linen and the silk were soaked for 24 hours prior to immersion in the indigo vat. For the linen blend an artificial urine vat was used (for sanitation and to save time). However, it was late summer/early fall, and only a few dips were possible between fermentations before it was too cold for the vat to continue fermentation. Only a modest light blue was achieved on the linen fabric. With the silk fabric, a lye-hydrosulfide vat was used because of time constraints, and because it was easier to control the reduction of the indigo. This is a more modern method, but it is also less damaging to the silk. We darkened the silk by mordanting it in iron, which grayed out the shade. There were over 20 dips on the silk fabric.

The Footwear

Both slippers and boots can be found in an illumination of the 14th century on women. Our shoes were based on the styles found as part of the traditional folk costume, which strongly resemble those in period works of art. The shoes themselves are made of pre-dyed leather, sewn with waxed linen thread. The pattern for the leather part is made in two pieces, and the resulting shoe strongly resembles slippers found in period illustrations. The knitted anklets are also based on those found attached to the boots of folk garments, and give the shoe a boot like profile, which is also documentable to the period, although it is impossible to tell if there are socks or knitted cuffs that create this effect.

The designs in the knitted anklets are taken directly from patterns in extant pieces, and have been executed in hand spun cotton combined with the hand dyed silk threads also used in the tiraz bands. Wool and cotton were often used in combination in multicolored patterned knitting in medieval Egypt and the surrounding areas. Many examples of pre-1500 fine gauge (17-36 stitches to the inch) multicolored patterned knitting are extant. White and blue cotton were common, with most of the other colors being executed in wool. These anklets were produced using handspun 2-ply cotton, in natural white and indigo dyed blue. More color was added by using the silk yarns, since these were available in colors matching the rest of the costume, although wool is more common in the extant pieces. The gauge of the anklets is 9-10 stitches per inch, which is coarser than most of the pieces we examined, but this was as fine as was possible with the tools available. A finer gauge would have required a longer stapled cotton, more cotton spinning experience, and finer knitting needles. Also the spinning was done on a modern charka wheel, an Indian wheel designed for spinning cotton, rather than a drop spindle. This was due to time constraints for the project, since the wheel was considerably faster than drop spinning cotton.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The Miraculous Journey of Mahomet, Miraj Nameh

Persian Poetry, Painting & Patronage, Marianna Shreve Simpson, 1998

Cut my Cote, Dorothy K. Burnham, Royal Ontario Museum

Islamic Textiles, Patricia Baker, 1995

Timur and the Princely Vision, Glen Lowrey & Thomas W. Lentz, 1989

Renaissance of Islam: Art of the Mamluks, Esin Atil, 1981

Art of the Persian Courts, Abolala Soudavar Rizzoli, 1992

“The Pattern of a Caftan, Said to Have Been Worn by Selim II (1512-20),” Janet Arnold in Costume, 1-2 (1967-68), pp.63-66

“The Clothing of a 14th Century Nubian Bishop,” Elizabeth Crowfoot in Studies in Textile History, Veronika Gervers, ed., 1977, pp. 43-51

“Tiraz Fabrics,” Veronkia Gervers & L. Golombek in Studies in Textile History, Veronika Gervers, ed., 1977, pp. 82 et.seq.

“A Romano-Egyptian Dress of the First Century B.C.,” Elizabeth Crowfoot in Textile History, 20 (1989), pp. 123-128

“A Medieval Face Veil from Egypt,” Gilian Eastwood in Costume, 17 (1983), pp. 33-38

“Medieval Garments in the Mediterranean World,” Veronika Gervers in Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe, N.B. Harte & K.G. Ponting, eds., 1983, pp. 297-315

Coptic Textiles in the Brooklyn Museum, Deborah Thompson, 1971

“Two Children’s Galabiyehs from Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt,” Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood in Textile History, 18 (1987), pp. 133-142

Persian Painting, Stuart Cary Welch

Art and Architecture of Islam 650-1250, Richard Ettinghausen and Oleg Graber

Islamic Art of Patronage: Treasures of Kuwait, Esin Atul, ed., 1990

The Arts of Islam: Masterpieces of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982

Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Richard Ettinghausen, 1972

Arab Painting, Richard Ettinghausen, 1962

Art of the Arab World, Esin Atil, 1975

Women in Islam, Wiebke Walther, 1981

Tissus D’Egypte, Collection Bouvier, 1993

The Book of Silk, Philippa Scott, 1993

Textiles from Medieval Egypt, A.D. 300 – 1300, Thelma K. Thomas, 1990

Decorative Arts of Arabia, Prisse D’Avennes

Art of Islam, Carel J. Du Ry

Arab Dress, Yedida Stillman, 2000

Early Islamic Textiles, Clive Rogers, ed., 1983

Secondary Sources

Veccelio’s Renaissance Costume Book (16th century), Cesare Vecellio, republished 1977

Costume in Antiquity, James Laver, 1963

Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume, Mary J. Houston, 1920

The Art of Arabian Costume, Heather Colyer Ross, 1981

Oriental Costumes, Max Tilke, 1922

Palestinian Costume, Shelagh Weir, 1989

The World of Islam, Bernard Lewis, ed.

Women’s Costume of the Near and Middle East, Jennifer Scarce

The Cut of Bedouin Jewelry, Heather Colyer Ross

How to Make Your Own Moccasins, Sylvia Grainger

Bedouin Jewelry in Saudi Arabia, Heather Colyer Ross

Behind the Veil, Fatima Mernassi

Costume Pattern and Design, Max Tilke, republished 1990

“The Dress of the Shajevan Tribespeople of Iranian Azerbaijan,” by Nancy Lindisfarn-Tapper in Languages of Dress in the Middle-East, Nancy Lindisfarne-Tapper & Bruce Ingham, eds., 1997

“An Ode to Woad”; Spin-off, 21(2): 86-92, Bobbie Irwin, 1997

The Art and Craft of Natural Dying, J. N. Liles ISBN: 0-87049-670-0., 1990

“Saxon Green: An Introduction”; Spin-off, 21(2): 83-85, Nancy Skinner, 1997

Arabic Proverbs, with Side by Side English Translations, Joseph Hanke, 1998

The Techniques of Tablet Weaving, Peter Collingwood, 1996.

A History of Hand Knitting, Richard Rutt, 1987.

Fig. 2 A female servant attending a birth: From the Maqamat of al-Hariri painted by the same artist, Iraq 1237. This woman wears a simple gown with a round neck that has decorative bands on the upper sleeves. Her white pants show beneath, as the garment has been drawn up with a belt. Note the veil with what appears to be a decorative band along the upper edge of the face. This type of garment and veil were used as a model for the undergarments we made for the costume.

Fig. 3 A pilgrim: I have included this picture because it is such a good illustration of the shoes. The man is wearing either high-topped shoes or low boots, with a flared or rolled top. They mold well to the feet and have slightly pointed toes. This is the only illustration I have found of walking shoes, as opposed to the court slippers seen in most pictures. This illustration is also from the same text as those above. Just like many pictures of Christian pilgrims, he carries a staff, lantern, and a large purse.

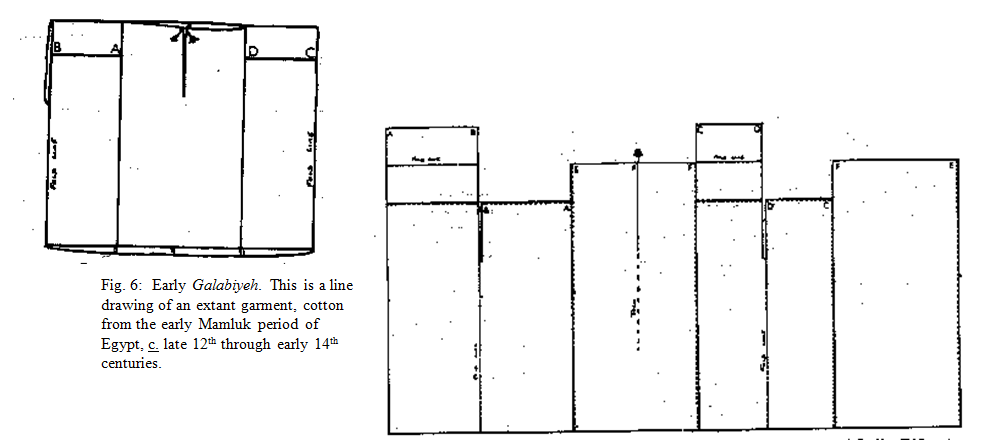

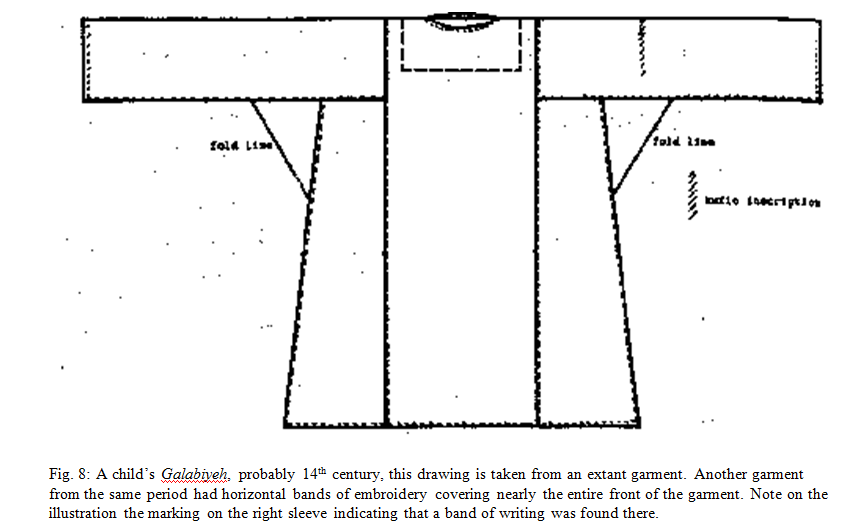

Extant pieces and patterns of extant garments

Fig. 7: Pattern of the garment to the left. Note how the rectangular pieces are put together.

Modern and "folk" garments

Modern North African woman. Note the colors of her fabrics and the piecing.

Modern shoes with attached socks in top photo, and separate socks in lower. The Top pictured shoe is very similar to the pilgrims walking shoes in construction.

Folk embroidery showing the pomegranate pattern.