Survey of Early Medieval Nubia 600 to 1000 C.E.

Mistress Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 1993)

Introduction: The Nubians of this period were an independent people, who for a period of almost 500 years had a wealthy, influential and thriving civilization, which has, unfortunately, fallen into obscurity. Scholarly research on medieval Africa in general is lacking, and where it does exist, it centers on the great cities on the Western coast. Nubia, a kingdom that was Christianized while most of Europe was still pagan, has been forgotten. Unfortunately, a third of it is now under water as well. The building of the Aswan dam in the 1960s has flooded towns, monasteries, cathedrals, and grave yards, which are now lost forever. The research that I did was time consuming and painstaking, but what emerged was an exciting picture of a fascinating culture. I hope you will agree.

Mistress Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 1993)

Introduction: The Nubians of this period were an independent people, who for a period of almost 500 years had a wealthy, influential and thriving civilization, which has, unfortunately, fallen into obscurity. Scholarly research on medieval Africa in general is lacking, and where it does exist, it centers on the great cities on the Western coast. Nubia, a kingdom that was Christianized while most of Europe was still pagan, has been forgotten. Unfortunately, a third of it is now under water as well. The building of the Aswan dam in the 1960s has flooded towns, monasteries, cathedrals, and grave yards, which are now lost forever. The research that I did was time consuming and painstaking, but what emerged was an exciting picture of a fascinating culture. I hope you will agree.

- Geography: North from Aswan in Egypt to Khartoum in Sudan in the south, east from the Red Sea to the Libyan desert to the west.

- Geopolitical background

- The area was first described as Nubia by Strabo (64 B.C.E.--24 C.E.), prior to this the area was know as Kush. The last dynasty of Egypt was the Kushite Dynasty, which ended in the 2nd century C.E. The rulers were Hamites (Egyptians) who lived in this area.

- Nubia was never a Roman province. Indeed, Rome showed little interest in conquering the area, though it did have extensive trade there.

- Black tribes began moving into the area in the 4th century C.E., and the area broke up into small chieftainships. They eventually conquered the peoples living there and set up their own government and culture.

- The first Nubian culture to reemerge in the 2nd century was the “Ballana” or Meroitic culture, which was centered in lower Nubia--what is northern Sudan today. It adopted some of the trappings of the earlier Kushite Dynasty, and incorporated this into a unique culture that was also influenced by the Byzantines and Indian culture.

- The Meroe culture was centered in the city of Meroe, 120 miles north of Khartoum.

- They were strongly influenced by Indian culture through their trade with that country. They traded in gold, ivory, slaves, animal pelts, ostrich feathers, and gums for spices, silver and other items.

- They had both a hieroglyphic writing and a cursive, phonetic script.

- They used iron weapons and tools.

- This Meroitic culture was the basis for what became the Christian Kingdom of Nubia.

- The Nubian Kingdoms of Nubia (upper Nubia), centered at Dongola, and Alwa (lower Nubia), whose capitol was at Soba, converted to Monophysite Christianity in the 6th century C.E., and became the early medieval Nubia that we will discuss here.

- Politics

- Nubia had a feudal government. The subjects were referred to as the “slaves” of the monarch, but this was a legal fiction. Feudalism was very loose in form until the 12th century.

- The government functioned with little in the way of written documents. No written legal code.

- Inheritance of kingship was from the king to his sister’s son. This made the Queen Mothers very important people--frequently no business of government could be conducted without their approval.

- The royalty practiced matrilineal cousin marriage--a hold over from dynastic times.

- Kings used the Greek title “Ourou.” Palace life was similar to that in the Byzantine empire. All functionaries used the Greek titles.

- The kings were also considered to have a religious function, as did the viceroy--a sort of prime minister. This official was called the “eparch” and given the title “Lord of the Horses.” He wore a ceremonial two horned headdress which is reminiscent of the crown of Isis.

- Nubia was attacked by Arab Muslims the first time in 641 C.E. These attacks ended for a while with the Treaty of Baqt, which was more or less respected by both sides between 700--1100. The treaty set up trade agreements, forbad Nubians to live in Egyptian held lands, and required Nubians to turn over run away slaves.

- The Crusades had a serious military impact on Nubia, because they put pressure on the Muslim Arabs to move south.

- After this time, their territory began to be whittled away by Muslim forces. The kingdom of Nubia ceased to exist in 1366, but the area was not entirely Islamic until 1504.

- An invasion by Shaug ed-Dowla in 1172 led to greater security measures in the country. Feudalism became formalized, and walls were built around cities and towns. Castle building began.

- The Nubians were known for the might of their army. The military were called “pupil smiters” by their enemies because of the accuracy of their archers. There is little actual archeological evidence of warfare save some border disputes with the Muslims and skirmishes with the Beja people in the Red Sea hills--a gold mining area.

- The military was mostly used for economic purposes.

- They protected trade routes through the country--for a fee.

- They raided in Ethiopia for slaves--the major Nubian export. Nubian slaves are not from Nubia, but were those slaves sold by the Nubians--mostly Ethiopians and Sudanese.

- The military was mostly used for economic purposes.

- The early period of Nubian history was a period where the country was very egalitarian, prosperous and where individuals had a great deal of personal freedom. It was the high point of culture, art, learning and religion.

- Culture

- Language

- The language spoken was Nubian, and an alphabet was developed for it in the 8th century. This was apparently done for convenience for words that didn’t translate well. No known documents in written Nubian.

- Written language was mostly Greek and Coptic. Badly spelled Greek graffiti has been found on city walls. Greek was the language of the clergy and the language found on tombstones.

- Letters were written on leather, important documents on parchment. Important documents were attractively illuminated in what is believed to be the Byzantine fashion with ornate head pieces and pictures of the saints. The treaty of Baqt was written in Greek and Arabic.

- Nubia was never a widely literate society. The writing that was done, was handled by clerics and a few government functionaries. The common people probably depended on the priests for letter writing.

- There is a strong indication of an oral tradition in story telling--especially since stories still exist today that have obvious roots in very early periods.

- Towns--Nubia had several large cities, which resembled Greek cities of the day. But most of the population lived in small towns on the banks of the Nile or the Red Sea.

- These towns had a nucleus of public buildings, a market square, taverns, public latrines, and at least one church.

- Buildings were built of mud brick with thatch or straw mat roofs. They were rectangular with small high windows. Benches were built into the walls. Private house had personal grain silos attached, and a narrow corridor that led to a private latrine.

- Buildings were (and still are) decorated in vivid colors in geometric and stylized life form designs.

- Most towns had a cottage industry such as : weaving wool fabric, leather production, palm fiber and reed weaving, pottery, or iron works.

- The economy was predominantly based on small scale farming.

- Where monasteries were found, there was also wine making, which was their major economic endeavor.

- Walled cities were unusual before 1000, but became increasingly seen after that.

- Economy

- Small scale farming with export of some local items.

- Irrigation was important and was accomplished with water wheels and bucket lifts.

- Local trade in food products.

- Main export was slaves--very lucrative, mostly with Egypt. Also brightly dyed, striped wool fabrics--known as Nubia cloth.

- The Nubians probably used a vertical loom, possibly slanted. The weft is beaten down, rather than up as was the case in most northern cultures. It is most likely that their looms were stretched between two beams rather than being warp-weighted.

- Nubians had access to many colorful dyes, and their fabrics were known for the use of brightly colored stripes.

- Small scale farming with export of some local items.

- Imports: linen, horses and wine from Egypt, luxury items from Egypt and Byzantium. Foods and spices from everywhere.

- Crafts

- Pottery--elaborate designs and bright colors. Use of geometrics and zoomorphic design elements. All types of vessels: amphorae, oil lamps, bowls and cooking pots.

- Leather craft--sandals and personal items

- Palm and reed weaving--sandals, hats and construction materials

- Iron mongering--tools, cooking utensils and personal items

- Art--early medieval Nubia had a renaissance of art, especially painting.

- Most paintings we know of today are frescos from the great cathedrals. The style is called “Violet style”

- Characteristics: brilliant colors, realistic portraiture

- Paintings of religious nature bear strong resemblance to the Byzantine style of painting during the period.

- Paintings of real people, such as funerary portraits and commemorations, were extremely realistic. Mummies have been able to be identified by their resemblance to the funerary portraits.

- Manuscript painting--in the Byzantine style with ornate capitals and pictures of the saints.

- Overview

- Nubia was religiously and ethnically diverse. The black Christian majority had no privileges over others living there.

- The importance of matrilineal descent and women in this culture should not be underestimated. Despite nominal male control over government and religion, women tended to be the center of village life, and were frequently consulted on spiritual matters. This did not change until the adoption of Islam.

- Economically, Nubia was quite well off. The standard of living for a villager was extremely good, and allowed for the purchase of luxury items and leisure time. Personal taxes were low because the King taxed trade items and had the monopoly on the slave trade.

- City life was very cosmopolitan, and similar in many respects to the large Greek cities of the period. City dwellers were usually tradesmen, diplomats, merchants, and clerics. The Court was centered in cities, and though it was set up on the Byzantine scheme, it was never large. The number of courtiers was very small in comparison to its Greek equivalent.

- Religion

- Prior to conversion to Christianity, most Nubians were worshipers of Isis, a remnant of the earlier religion in the area.

- Isis worship was centered in Northern Nubia at the temple on the island of Philae.

- Remnants of this worship continued to be seen in some of the ceremonial life of Nubians--love of perfumes and incense, and sacrifices of dates, believed to symbolize fertility. Also in animal symbols such as the crocodile, which was believed to be good luck.

- Prior to conversion to Christianity, most Nubians were worshipers of Isis, a remnant of the earlier religion in the area.

- The three major areas of Nubia were converted by 580 C.E.

- Early missionary work in the area was done by Bishop John of Ephesus.

- Nubians practiced Monophysite Christianity in a form similar to the Copts of Egypt. However they used Greek in their services like the Byzantines.

- Pagan temples were converted to Christian churches early on--in the late 6th century. Burial with funerary objects ended with the conversion to Christianity.

- Nubia is said to have converted to the Monophysite form of Christianity through the influence of Empress Theodora of Byzantium, who came to be a cult figure in Nubia. Traditional story about Justinian and Theodora competing for the conversion of Nubia to their forms of Christianity.

- They also had a mythology that is probably a remnant of their tribal culture before moving into the area. This mythology had to do with the world of supernatural beings and spirits. The basic ideas in the mythology date at least back to Meroitic times (2nd-4th cent. C.E.).

- Spirits of the Nile--river angels or water people. These creatures are believed to live below the surface of the Nile. In some ways this folklore is similar to that in Europe about the land of Faerie.

- The beneficial spirits are the river angels and the evil ones are the “dogri.” Although these spirits all have tangible human like forms, the dogri are believed to be shape shifters who feed on human flesh. A sort of Nubian vampire.

- Certain substances were believed to placate the spirits---perfume, incense and dates. Certain substances attracted spirits--blood and gold.

- Washing in the Nile or casting in objects for the spirits is an important part of many ceremonies--marriage, childbirth.

- Possession by spirits--possession cults, predominantly female, exist in Sudan and Ethiopia today. They are believed to predate both Islam and Christianity. Trance dancing is found in both of these cults.

- Spirits of the Nile--river angels or water people. These creatures are believed to live below the surface of the Nile. In some ways this folklore is similar to that in Europe about the land of Faerie.

- Nubia was religiously diverse. They had Orthodox Christians, Coptic Christians and Jews all living in the major cities. Muslims were allowed to live in Nubia, but could not proselytize--wars with the surrounding Islamic states made the Nubians wary of Muslims. They were allowed to worship at the mosques.

- The Nubian culture was matrilineal, and even though men ruled and ran the government of the Church, women never lost their significance as spiritual beings in Nubian culture.

- Churches were built in the basilican style. One of the great cathedrals was the one at Faras, built in 7th century and rebuilt around 700 C.E. The murals there date from 750-1050.

- The Church officials wore the robes of the Monophysites--not those of the Orthodox.

- Everyday life

- Food--a wide variety of foods were available in the Nubian diet. Desertification had not yet reduced arable land, and enough food was grown for both domestic use and export. No recipes of the period survive, but there are good trade records.

- Ingredients: coffee (from Ethiopia where it originated), lamb, fish, lentils, okra, onions, rice, barley, ground nuts (similar to peanut), banana, coconut, taro, yams. Cane sugar became available in the 6th century.

- Spices--cloves (native), garlic, sesame, cumin. Imported cinnamon and cardamon.

- Native dishes--tej (honey wine), date wine, flat bread (like a tortilla), beer called “bouza”--perhaps where we get the word “booze.”

- Wines--Nubia had a wine making and wine drinking culture. Wines were made locally by monasteries and also imported from Egypt--where they could be made but not drunk under Islamic law. Amphorae have been found in great quantity, and every village had a tavern. Pottery was decorated with grape and vine designs.

- Clothing and ornament

- Undergarments of linen imported from Egypt with over garments or mantles of brightly colored and ornately striped wool fabric. A linen garment with a wool mantle was probably the everyday dress of most Nubian villagers.

- They wore sandals of leather or woven palm, woven or leather belts. Hats and or veils were probably worn. Large woven palm hats for work, and possibly skull caps and veils for worship.

- Women corn-rowed their hair, men wore theirs short. Small beards and mustaches are seen in portraits of royalty and on Bishops, but it is unknown if everyday people adopted this fashion.

- Beads or local materials were used as jewelry. Most women had pierced ears and wore earrings of silver or gold if they could afford it. Other jewelry items were either made locally of iron or imported.

- Activities

- Farming, small scale industry, and trade up and down the Nile were the major economic activities of people in the towns.

- Socializing--taverns, and a town square as well as other public buildings allowed for an active town social life. Marriages, funerals and the birth of children were events that the whole community would participate in.

- Story telling

- Drinking

- Child care

- House painting--houses were ornately painted, as they are today. This is frequently a social event where friends and neighbors join in.

- Cooking and coffee drinking--often a social event in village cultures

- Religious worship--church going was an important activity in Nubian culture. Most Nubians went to church daily to hear mass.

- John the Deacon c. 770, al-Baladhuri c. 890, al-Tabari 839-923, Ibn Khaldun 1332-1406, al-Maqrizi 1364-1442.

- Also unknown Arab and Muslim historians and geographers, some Christian writers, indigenous theological writings.

- Archeological digs from the 1960s.

- Page from an Illuminated Gospel, early 15th cent. Ethiopian, seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Secondary Sources

Africa in Antiquity: The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan, vol. I; The Brooklyn Museum (1978)

African Cooking; Laurens van der Post (1970)

The African Cookbook; Bea Sandler (1970)

The African News Cookbook: African Cooking for Western Kitchens; Tami Hultman, ed. (1985)

African Religions and Philosophy; John S. Mbiti (1970)

Ancient African Kingdoms; Margaret Shinie (1965)

Ancient Egyptian and Greek Looms; H. Ling Roth (1913)

The Book of Costume; Millia Davenport (1948)

The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 2; J.D. Fage, ed. (1978)

Ceramic Industries of Medieval Nubia, vols. I & II, William Y. Adams

Coconuts; Jasper Guy Woodroof (1970)

“Coptic Sandals,” from Early Period, vol. VIII, pg. 16 (privately published); Rebecca Wendelken

“Coptic Tunics,” from Early Period, vol. I, pg. 21 (privately published); Rebecca Wendelken

Costume and Fashion, vol. I; Herbert Norris (1930)

“The Development of European Footwear from the Fall of Rome to the Renaissance,” from CIBA Review, #34, June 1940, pg. 1221; W. Born

Egypt After the Pharaohs: 332 B.C.--642 A.D.; Alan K. Bowman (1986)

Embroiderers; Kay Staniland (1991)

Food: The Gift of Osiris,vols 1&2; William J. Darby, et.al. (1977)

Food in History; Reay Tannahill (1973)

High Dam Over Nubia; Leslie Greener (1962)

Jewelry: 7000 Years; Hugh Tait, ed. (1987)

Kitchen Safari; Harva Hachten (1970)

Nubian Ceremonial Life; Juon G. Kennedy, ed. (1978)

Nubia: Corridor to Africa; William Y. Adams (1977)

Nubian Rescue; Rex Keating (1975)

Nubian Twilight; Rex Keating (1975)

Nubians in Egypt: Peaceful People; Robert A. Fernea (1932)

The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Edition; J.A. Simpson & E.S.C. Weiner, eds. (1989)

Peanuts; Jasper Guy Woodroof (1973)

The Spice Trade of the Roman Empire, 29 B.C. to A.D. 64; J. Innes Miller (1969)

Temples and Tombs of Ancient Nubia; Torgny Save-Soderbergh, ed.

Vintage: The Dtory of Wine; Hugh Johnson (1989)

The Weaving, Spinning, and Dying Book; Rachel Brown (1978)

Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men, and the Zar Cult in Northern Sudan; Janice Boddy (1989)

A World of Embroidery; Mary Gostelow (1975)

Africa in Antiquity: The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan, vol. I; The Brooklyn Museum (1978)

African Cooking; Laurens van der Post (1970)

The African Cookbook; Bea Sandler (1970)

The African News Cookbook: African Cooking for Western Kitchens; Tami Hultman, ed. (1985)

African Religions and Philosophy; John S. Mbiti (1970)

Ancient African Kingdoms; Margaret Shinie (1965)

Ancient Egyptian and Greek Looms; H. Ling Roth (1913)

The Book of Costume; Millia Davenport (1948)

The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 2; J.D. Fage, ed. (1978)

Ceramic Industries of Medieval Nubia, vols. I & II, William Y. Adams

Coconuts; Jasper Guy Woodroof (1970)

“Coptic Sandals,” from Early Period, vol. VIII, pg. 16 (privately published); Rebecca Wendelken

“Coptic Tunics,” from Early Period, vol. I, pg. 21 (privately published); Rebecca Wendelken

Costume and Fashion, vol. I; Herbert Norris (1930)

“The Development of European Footwear from the Fall of Rome to the Renaissance,” from CIBA Review, #34, June 1940, pg. 1221; W. Born

Egypt After the Pharaohs: 332 B.C.--642 A.D.; Alan K. Bowman (1986)

Embroiderers; Kay Staniland (1991)

Food: The Gift of Osiris,vols 1&2; William J. Darby, et.al. (1977)

Food in History; Reay Tannahill (1973)

High Dam Over Nubia; Leslie Greener (1962)

Jewelry: 7000 Years; Hugh Tait, ed. (1987)

Kitchen Safari; Harva Hachten (1970)

Nubian Ceremonial Life; Juon G. Kennedy, ed. (1978)

Nubia: Corridor to Africa; William Y. Adams (1977)

Nubian Rescue; Rex Keating (1975)

Nubian Twilight; Rex Keating (1975)

Nubians in Egypt: Peaceful People; Robert A. Fernea (1932)

The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Edition; J.A. Simpson & E.S.C. Weiner, eds. (1989)

Peanuts; Jasper Guy Woodroof (1973)

The Spice Trade of the Roman Empire, 29 B.C. to A.D. 64; J. Innes Miller (1969)

Temples and Tombs of Ancient Nubia; Torgny Save-Soderbergh, ed.

Vintage: The Dtory of Wine; Hugh Johnson (1989)

The Weaving, Spinning, and Dying Book; Rachel Brown (1978)

Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men, and the Zar Cult in Northern Sudan; Janice Boddy (1989)

A World of Embroidery; Mary Gostelow (1975)

Bibliography of Costume Sources

Africa in Antiquity: The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan, vol. 1; The Brooklyn Museum, 1978

African Kingdoms; Basil Davidson, 1971

Ancient African Kingdoms; Margaret Shinie, 1965

Ancient Egyptian and Greek Looms, H. Ling Roth, 1913

The Book of Costume; Millia Davenport, 1948

The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 2; J.D. Fage, ed., 1978

Ceramic Industries of Medieval Nubia, Part I; William Y. Adams, 1986

Costume and Fashion, vol I; Herbert Norris, 1930

"Coptic Sandals," Early Period, vol. VIII, pg. 16; Rebecca Wendelken

"Coptic Tunics," Early Period, vol. I, pg. 21; Rebecca Wendelken

"The Development of European Footwear from the Fall of Rome to the Renaissance," CIBA Review #34, June 1940, pg. 1221; W. Born

Egypt after the Pharaohs: 332 B.C.--642 A.D.; Alan K. Bowman, 1986 High Dam Over Nubia; Leslie Greener, 1962

Jewelry: 7000 Years; Hugh Tait, ed., 1987

Nubia: Corridor to Africa; William Y. Adams, 1977

Nubian Ceremonial Life; John G. Kennedy, ed., 1978

Nubian Rescue; Rex Keating, 1975

Nubian Twilight; Rex Keating, 1975

Nubians in Egypt: Peaceful People; Robert A. Fernea, 1932

Simple Weaving; Marthann Alexander, 1954

Temples and Tombs of Ancient Nubia; Torgny Save-Soderbergh, ed., 1987

The Weaving, Spinning, and Dying Book; Rachel Brown, 1978

A World of Embroidery; Mary Gostelow, 1975

Africa in Antiquity: The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan, vol. 1; The Brooklyn Museum, 1978

African Kingdoms; Basil Davidson, 1971

Ancient African Kingdoms; Margaret Shinie, 1965

Ancient Egyptian and Greek Looms, H. Ling Roth, 1913

The Book of Costume; Millia Davenport, 1948

The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 2; J.D. Fage, ed., 1978

Ceramic Industries of Medieval Nubia, Part I; William Y. Adams, 1986

Costume and Fashion, vol I; Herbert Norris, 1930

"Coptic Sandals," Early Period, vol. VIII, pg. 16; Rebecca Wendelken

"Coptic Tunics," Early Period, vol. I, pg. 21; Rebecca Wendelken

"The Development of European Footwear from the Fall of Rome to the Renaissance," CIBA Review #34, June 1940, pg. 1221; W. Born

Egypt after the Pharaohs: 332 B.C.--642 A.D.; Alan K. Bowman, 1986 High Dam Over Nubia; Leslie Greener, 1962

Jewelry: 7000 Years; Hugh Tait, ed., 1987

Nubia: Corridor to Africa; William Y. Adams, 1977

Nubian Ceremonial Life; John G. Kennedy, ed., 1978

Nubian Rescue; Rex Keating, 1975

Nubian Twilight; Rex Keating, 1975

Nubians in Egypt: Peaceful People; Robert A. Fernea, 1932

Simple Weaving; Marthann Alexander, 1954

Temples and Tombs of Ancient Nubia; Torgny Save-Soderbergh, ed., 1987

The Weaving, Spinning, and Dying Book; Rachel Brown, 1978

A World of Embroidery; Mary Gostelow, 1975

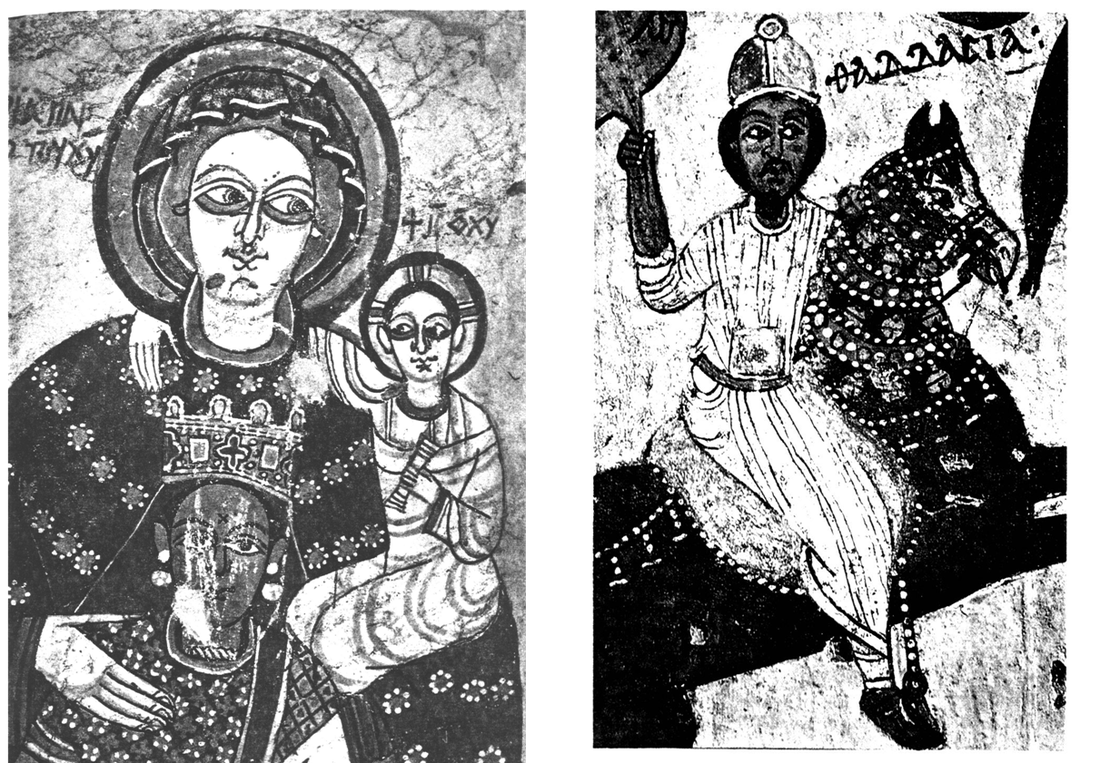

Pictures of extant paintings, drawings, and artifacts

On the left is a Nubian Queen portrayed with the Madonna and child. On the right is a King riding into battle. These murals were found in the remnants of a cathedral. Religious figures were portrayed stylized, similar to the Byzantines, while actual people were painted realistically.

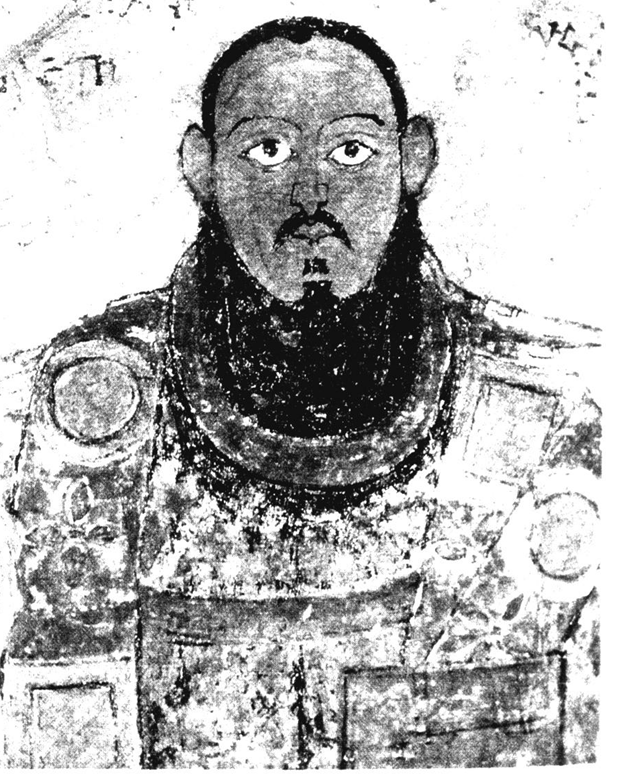

A Nubian bishop's funerary portrait. Due to mummification of the body, it was easy to identify as it still resembled the portrait. The clothing, assuming it is clerical, resembles the Byzantine and Coptic traditions.

The remains of a Nubian church from the inside.

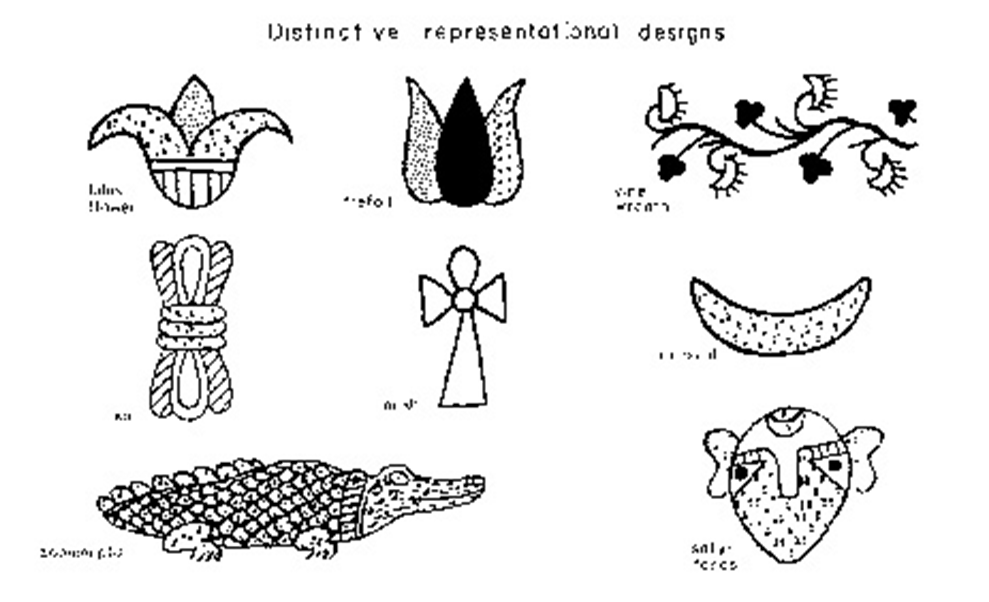

Design motifs found on a variety of extant objects.

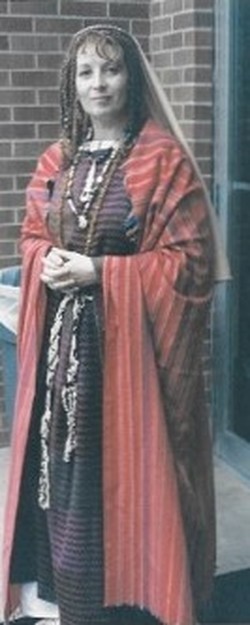

Your author wearing a Nubian costume of the middle-class.