The Persian Coat: 14th--16th Centuries C.E.

Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 2000)

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The Miraculous Journey of Mahomet, Miraj Nameh

Persian Poetry, Painting & Patronage, Marianna Shreve Simpson, 1998

Cut my Cote,, Dorothy K. Burnham, Royal Ontario Museum

Islamic Textiles, Patricia Baker, 1995

Timur and the Princely Vision, Glen Lowrey & Thomas W. Lentz, 1989

Renaissance of Islam: Art of the Mamluks, Esin Atil, 1981

Art of the Persian Courts, Abolala Soudavar Rizzoli, 1992

AThe Clothing of a 14th Century Nubian Bishop,@ Elizabeth Crowfoot in Studies in Textile History, Veronika Gervers, ed., 1977, pp. 43-51

AMedieval Garments in the Mediterranean World,@ Veronika Gervers in Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe, N.B. Harte & K.G. Ponting, eds., 1983, pp. 297-315

Persian Painting, Stuart Cary Welch

Art and Architecture of Islam 650-1250, Richard Ettinghausen and Oleg Graber

Islamic Art of Patronage: Treasures of Kuwait, Esin Atul, ed., 1990

The Arts of Islam: Masterpieces of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982

Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Richard Ettinghausen, 1972

Women in Islam, Wiebke Walther, 1981

The Book of Silk, Philippa Scott, 1993

Secondary Sources

Veccelio's Renaissance Costume Book (16th century), Cesare Vecellio, republished 1977

Costume in Antiquity, James Laver, 1963

Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume, Mary J. Houston, 1920

Oriental Costumes, Max Tilke, 1922

The World of Islam, Bernard Lewis, ed.

Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East, Jennifer Scarce

Behind the Veil, Fatima Mernassi

Costume Pattern and Design, Max Tilke, republished 1990

Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia (copyright Micaela Burnham 2000)

- Origins

- Middle-Eastern: Similar is cut to the thôbs worn throughout the middle east from at least the 13th century, and probably before. The beginnings of this garment can be found in extant garments from Egypt c. 6th-7th cents. C.E. Some costume historians believe that this pattern arose in Persia and spread to the rest of the Middle East. I believe that the Persians added their own touch to garments already found, and these became widespread.

- Chinese: Patterns, fabrics, front opening, overhung sleeves and some headdresses all show definite influence of Mongols/Chinese. The invasion of Genghis Khan’s Mongols in the 12th century began the introduction of many Oriental elements into Persian costume.

- By the beginning of the Timurid Dynasty in the 14th century, Persian costume had developed its own unique style. Elements of this are the “cloud collar” and the overhung sleeves, as well as the button front openings. It involved an elegant flowing look and lots of layers, the use of scarves and shawls, and a large variety of headdresses.

- How It Was Worn

- Layering

- Chemise and pants constitute the first layer. Chemise is same cut but sewn shut from waist down, and usually narrower to keep it from binding up the feet. They sometimes had overhung sleeves, like the over garments. Pants are simple tubes with gussets added in crotch for freedom of movement and sizing.

- Persian coat long to the ankle with long sometimes overhung sleeves.

- There would usually be a second, and sometimes a third coat. These could be shorter, have short sleeves, lower necklines, and were usually left open at the bottom to show off the garment beneath. Frequently they would also be unbuttoned a few inches at the top and turned under--also to display the garments beneath. The outermost of the coats might have a cloud collar attached. This is a piece of ornate embroidery in gold and other colors that was placed around the neckline. They were always detachable and were made as separate garment, then sewn to the desired coat. (See handout.)

- A belt or sash was usually worn. This was most often a sash tied at the hips, but might be a leather belt.

- Over garments were common. The over garments were usually cut fuller, frequently lined in fur, and were most likely to have the exaggerated overhung sleeves. There are some over garment that appeared to be vest like, and others that resembled the European sideless surcoat. (See handout.)

- Headdresses, hats, and veils in a wide variety of styles were worn.

- Colors and Fabrics

- Most fabrics were silk, usually brocade (a figured textile in which the pattern appears to be raised and which gives the appearance of embroidery), lampas (a fabric where the main warp is brought to the surface of the cloth to form a pattern), or damask (a figured textile with one warp and one weft in which the pattern is formed by a contrast of binding systems), sometimes embroidered, sometimes plain. The plain silks were used for linings as well. Cottons and linens were known, but the Persian coat of the upper-class woman was made of silk, as were her chemise and pants, though these might be made of plain linen. The servants and lower classes wore linens, cottons, and wools. Many of these silks were imported from China and have a distinctly Asian look. Performers and dancer would have had some silk (mostly in veils and scarves), and the garments would mostly have been cotton or linen cotton blends or silk and cotton blends.

- Colors:

- Chemises and pants were usually white as this is easiest to launder. Examples are sometimes seen with pants being a different color, even black, but it’s believed that there was probably a white pair underneath, and the second layer may have been for warmth.

- Patterns and colors were used together that might not be considered good combinations today. Contrasting colors, plaids with stripes and solids, and layers of differing brocades were all common.

- Embroidery: The most famous examples are the cloud colors, made of gold thread work with colored silk thread accents. These are the only extant examples of embroidery, but paintings suggest that it was used elsewhere on garments and headdresses as accent work. Seam finishes may also have been embroidered, as this was a common technique on garments from later periods. Since no extant Persian coat has yet been found, there is much we still do not know about them.

- Pattern

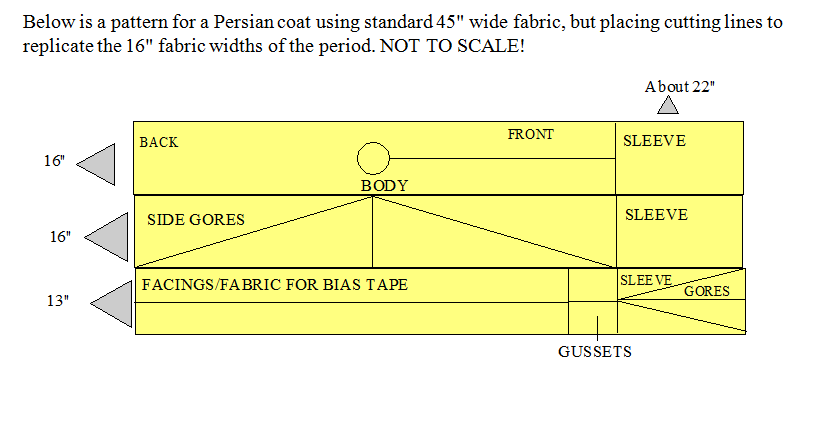

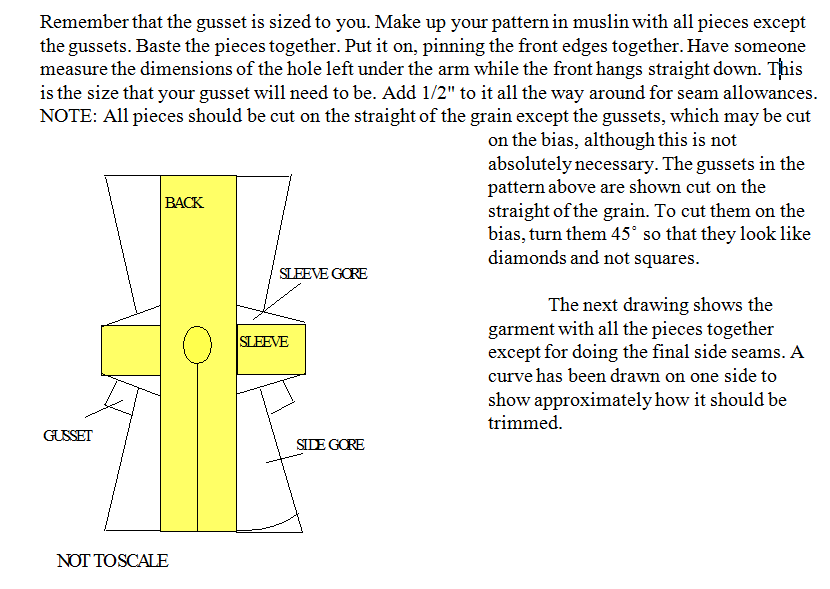

- The cut: The Persian coat was cut of fabric that was generally 16" wide. It is cut in non-curved, geometric pieces that allow for total use of the fabric without waste. (See hand-out) Sizing is done by altering the size of the gusset. For a very large person or a very full garment, another set of gores would be put into the side seams.

- Sewing technique

- All Persian coats are lined or, less common, faced. They may be either a standard or free falling lining or an underlining--also called flat lining.

- If using a standard lining where you make two garments, one of the outer fabric and one of the lining and then sew them together with the lining turned to the inside, you can finish seams by machine because they will not show. This is the most appropriate lining if you want the garment to be very drapeable and flowing, such as a dance garment.

- If doing interlining where you cut identical pieces of outer fabric and lining and sew them together at the same time, you will have exposed seam allowances inside the garment. With this you will have to finish the seams by hand with handstitiching or embroidery. If the lining is for an outer garment where the lining will be exposed, embroidered seam finishes are a nice touch. This is the most appropriate lining for formal garments with more body and stiff fabrics.

- Chemises and pants were not believed to be lined.

- The Persian coat is sewn together much like a kimono, except the shapes of the pieces are different. This is the order of construction:

- Sew the sleeve gores to each side of the length of the sleeves.

- Sew the sleeves to the body centering them with the neck hole.

- Sew the side gores to each side of the garment starting at the bottom. When you reach the sleeve gores, trim off the tops of the side gores leaving enough seam allowance to sew them to the sleeve gores.

- Sew the trimmed tops of the side gores to the bottom part of the sleeve gores.

- If you are adding facings to the opening in the front, sew these in now. Finish the neck edge. If you don’t want to use facings, bias tape, either purchased or cut from a contrasting fabric, makes a nice clean finish for you front edges. Do this now also. You may wish to wait before sewing down the inside edges of your facings and/or bias tape until after you have added your closures later on.

- Sew two sides of each gusset into triangular space created at the intersection of the sleeve and side gores on the front only.

- Trim the bottom hems to make a smooth curve that will make an even hem when the garment is finished.

- Fold the garment at the shoulder line, right sides together. Pin the rest of the garment together, fitting in the gussets into the triangular area on the back and working down the sleeves.

- Sew the side seams from the hem up to the gussets.

- Sew the sleeve seams from the cuff to the gussets.

- Finish sewing the gussets in place.

- Hang the garment over night. Trim the hem more if needed.

- If you are free lining the garment, sew it in place now.

- Hem the bottom and sleeve ends and add buttons and loops. Sew down the inside edges of the facings and/or bias tape.

- Do any seam finishes not done as you were going along.

- Sizes: Sizing is done by altering the size of the gussets. For a very large garment, put a second set of side gores in along the edge of the first set.

- Variations

- Necklines: Necklines were generally curved, but were cut at various heights. When worn, the neck edge of an over garment might be turned under to better reveal the garment beneath, which gives the appearance of a V neck. Some necklines may also have been cup this way.

- Sleeves: This is where a great deal of variation is seen. Here is a selection of varieties:

- Overhung sleeve--anywhere from just over the hand to several feet past the fingers. The very long ones most evident on over garments.

- Detachable sleeves--the very long sleeves might attach to the inside of a short sleeve by means of a button. This was also frequently seen in Mongol coats.

- Short sleeve--the same pattern, but ending above the elbow.

- Wing sleeve--Some over garments show a sleeve that resembles a wing or epaulette. Similar to a cap sleeve.

- Liripipe sleeves--short sleeves with long flowing extensions that hang from the back. Similar to the European sleeve of the same type.

- Buttons: Buttons were the main form of closure. They might be of fabric, metal, glass, pottery, wood, or knotted cord (like frogging). Frogging is seen in many depictions of the Persian coat. Most of the buttons found extant are in Turkey in the 16th cent. These were wooden beads or toggles that had been wrapped in thread. This was also a common technique in Europe, and is easy to master.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The Miraculous Journey of Mahomet, Miraj Nameh

Persian Poetry, Painting & Patronage, Marianna Shreve Simpson, 1998

Cut my Cote,, Dorothy K. Burnham, Royal Ontario Museum

Islamic Textiles, Patricia Baker, 1995

Timur and the Princely Vision, Glen Lowrey & Thomas W. Lentz, 1989

Renaissance of Islam: Art of the Mamluks, Esin Atil, 1981

Art of the Persian Courts, Abolala Soudavar Rizzoli, 1992

AThe Clothing of a 14th Century Nubian Bishop,@ Elizabeth Crowfoot in Studies in Textile History, Veronika Gervers, ed., 1977, pp. 43-51

AMedieval Garments in the Mediterranean World,@ Veronika Gervers in Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe, N.B. Harte & K.G. Ponting, eds., 1983, pp. 297-315

Persian Painting, Stuart Cary Welch

Art and Architecture of Islam 650-1250, Richard Ettinghausen and Oleg Graber

Islamic Art of Patronage: Treasures of Kuwait, Esin Atul, ed., 1990

The Arts of Islam: Masterpieces of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982

Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Richard Ettinghausen, 1972

Women in Islam, Wiebke Walther, 1981

The Book of Silk, Philippa Scott, 1993

Secondary Sources

Veccelio's Renaissance Costume Book (16th century), Cesare Vecellio, republished 1977

Costume in Antiquity, James Laver, 1963

Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume, Mary J. Houston, 1920

Oriental Costumes, Max Tilke, 1922

The World of Islam, Bernard Lewis, ed.

Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East, Jennifer Scarce

Behind the Veil, Fatima Mernassi

Costume Pattern and Design, Max Tilke, republished 1990

Directions for construction:

- Sew the sleeve gores to each side of the length of the sleeves.

- Sew the sleeves to the body, centering them with the neck hole.

- Sew the side gores to each side of the garment starting at the bottom. When you reach the sleeve gores, trim off the tops of the side gores leaving enough seam allowance to sew them to the sleeve gores.

- Sew the trimmed tops of the side gores to the bottom part of the sleeve gores.

- If you are adding facings to the opening in the front, sew these in now. Finish the neck edge. If you don’t want to use facings, bias tape, either purchased or cut from a contrasting fabric, makes a nice clean finish for your front edges. Do this now if you choose to use this finish. You may wish to wait before sewing down the inside edges of your facings and/or bias tape until after you have added your closures later on. If you are fully lining the garment, skip this step.

- Sew two sides of each gusset into the triangular spaces created at the intersection of the sleeves and side gores on the front only.

- Trim the bottom hems to make a smooth curve that will make an even hem when the garment is finished.

- Fold the garment at the shoulder line, right sides together. Pin the rest of the garment together, fitting in the gussets into the triangular area on the back and working down the sleeves.

- Sew the side seams from the hem up to the gussets.

- Sew the sleeve seams from the cuff to the gussets.

- Finish sewing the gussets in place.

- Hang the garment over night. Trim the hem more if needed.

- Hem the bottom and sleeve ends and add buttons and loops. Sew down the inside edges of the facings and/or bias tape. Alternatively, this is the time to sew in a free falling lining.

- Do any seam finishes not done as you were going along.